The automobile got its first taste of blood 125 years ago today — and it’s never been able to kick the habit.

On the evening of Sept. 13, 1899 — 125 years ago today — taxi cab driver Arthur Smith struck Manhattan resident Henry Hale Bliss on Central Park West, making him the first victim of a fatal car crash in the Western Hemisphere.

“The automobile has tasted blood,” wrote the Alton (Illinois) Evening Telegraph, pivoting to prescience: “It is now an engine of death.”

An engine of death. Behind those four evocative words are some astounding statistics amassed over the next 125 years. Since the killing of Henry Bliss, an estimated 3,996,409 people have died in automobile crashes in the United States, or roughly equivalent of the populations of Wyoming, Vermont, Alaska and North Dakota and South Dakota combined, with the city of Orlando thrown in for good measure.

In a good year, 40,000 Americans will die in a car crash, roughly 110 people every day. Imagine if an intercity jetliner crashed every day; the public response would be immediate and urgent. But scores of deaths merit a collective shrug.

“We don’t see traffic fatalities the same way as other public health crises. But getting on our roadways is the most dangerous thing we do every day, across the board,” Lorraine Martin of the non-profit National Safety Council recently told the journal Public Health.

The vast majority of the dead have been inside automobiles, of course, but tens of thousands have been pedestrians and cyclists.

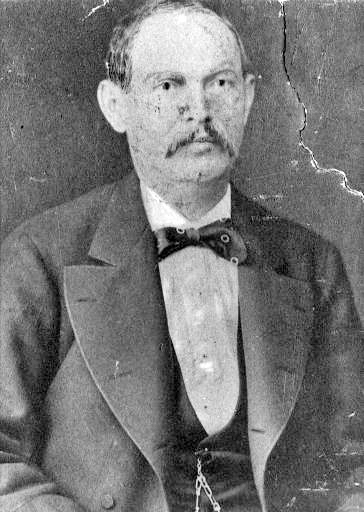

Of course, none of that had to happen. When Bliss — a prominent real estate man and grandson of a Vermont governor — was killed, automobiles were still a plaything of the rich, with just 2,500 cars manufactured in the United States that year.

But that would quickly change. By 1901, autos were seen as such a threat that Connecticut became the first state to create a speed limit: 12 mph in the city and 15 mph in the country. And for the first two decades of the automobile age, news coverage tended to be sympathetic to the victims of road violence, not its perpetrators.

“Nation Roused Against Motor Killings,” the Times reported.

But such tone in the media and in society changed with the mass-produced Ford Model T, which brought car ownership within reach of the middle-class in the 1920s.

By 1925, the victory of the car was complete: Los Angeles passes a no-jaywalking rule that becomes a national model.

As widely documented, car makers created the “crime” of “jaywalking” to insulate themselves and their product and their customers for blame for what the Times called “a huge problem.”

The nation’s switch from a “streets are for people, not cars” mentality to a “people are in the way of cars” mentality was hilarious — though accurately — satirized by Adam Conover on his show, “Adam Ruins Everything”:

From then on, engineers reconceived roadways to prioritize the speed of vehicles, as Peter Norton pointed out repeatedly in his book, “Fighting Traffic: The Dawn of the Motor Age in the American City” (MIT Press, 2011), and the nation created tens of thousands of miles of interstate highways.

Of course, Bliss’s death — which made newspapers from coast to coast — had nothing to do with “jaywalking,” but with basic road design. Before automobiles, the stretch of Central Park West was mostly traversed by trolleys and people using horses for locomotion, but that changed in the early part of the 20th century, as this historic shot shows:

Bliss alighted from a trolley that was heading in the direction of the cars in the photo above. But another vehicle blocked the curbside lane (ain’t it always the case?), so Smith, the taxi driver, veered into the center of the roadway, striking Bliss as he turned back towards the trolley to help his companion, who was identified only as a “Miss Lee.”

Even in 1899, the coverage showed that there are no accidents — just results of bad decisions by city planners and drivers.

“That section of Central Park West between 65th Street and 90th Street is known to drivers and motormen as ‘Dead Man’s Pass’ because of the accidents [sic] that happen there,” the Washington Times Herald reported.

The driver claimed he didn’t see Bliss step off the trolley — and by the time he did, it was too late to stop, the Brooklyn Times Union reported. None of the coverage documented Smith’s speed at the time of the crash.

The curiosity of Bliss’s death would quickly wear off. In 1910, the first year in which such statistics were kept, automobiles killed more than 100 pedestrians in New York City, a number that would double by 1912.

Now, we barely question pedestrian deaths, which most drivers and virtually all politicians treat as a cost of doing business in a bustling metropolis. In 1999, the city departments of Transportation and Parks held a commemoration at the corner of Central Park West and 74th Street, and put up a plaque in Bliss’s honor:

“This sign is erected to remember Mr. Bliss’s untimely death and to promote safety on our streets and highways,” the sign reads.

The city is not planning any commemoration today to mark the 125th anniversary. The Department of Transportation did not respond to a request for comment.