This article is the first in series about a pivotal moment in St. Louis’s sustainable transportation evolution, and how it mirrors similar moments in other U.S. cities. Click here for the entire series.

A couple of weeks ago, I went on a three-hour bike ride with the mayor of St. Louis.

To say that it’s unusual for the leader of a major U.S. city to spend that much time sweating in the saddle would be an understatement. But like many U.S. communities awash in American Rescue Plan Act funds and finally waking up to the ravages of traffic violence, this isn’t a typical time in the Gateway City.

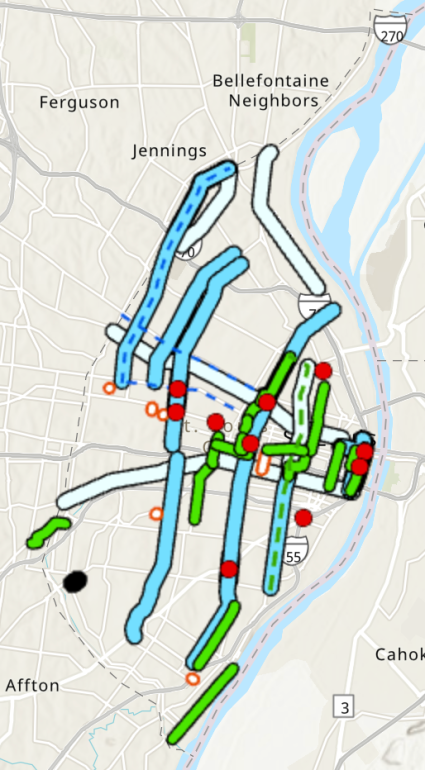

In recent months, my local government has quietly announced more than $300 million in street safety infrastructure set to come to our streets in the next three years, the sites of which Mayor Tishaura Jones toured alongside a loose flock of advocates, staffers, elected officials, and a single journalist: me. (In a city as small as St. Louis with an even smaller sustainable transportation community, it is safe to say that I count the majority of these people as my friends, neighbors, and fellow advocates, so please consider this a blanket disclosure that I have personal relationships with pretty much everyone in this story.)

That $300 million through 2027 — mostly a lucky confluence of rescue plan and other federal grants — is a staggering investment for a shrinking Rust Belt city whose total annual budget is just $1.3 billion. But it’s an even more staggering shift for a region with a reputation for being among the worst in America for people outside cars.

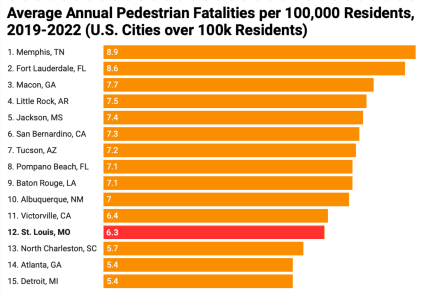

NHTSA data ranks St. Louis 12th among major U.S. cities with the highest per-capita pedestrian death rates between 2019 and 2022. Moreover, all the communities ranked above it are located in Sun Belt cities in the American south and west, where reliably warm weather makes walking possible year-round — unlike my city, whose residents have to contend with humid summers, rainy springs and icy winters, and often drive just to beat the elements.

Those pedestrian fatality numbers are even more stark in light of how many St. Louisans are simply terrified to travel outside a car even on good days — in no small part because of the constant threat of traffic violence.

“Parents are afraid to let their children play outside or walk or bike to school because they would have to navigate roads built for big, motorized vehicles,” Mayor Jones said in a statement to Streetsblog following the ride (it’s hard to get an accurate quote from behind a set of handlebars). “In St. Louis, it can be difficult to move from one neighborhood to another without getting in a car, because highways and large roads have created borders that feel daunting to cross without getting in a car yourself.

“In essence, our streets have been designed in ways that are dangerous, bad for our health, harmful to the environment, and disruptive to our neighborhoods,” she continued. “We are reversing that, making our transportation infrastructure people-friendly.”

A money surge, a culture shift

As I pedaled alongside Jones, who tackled the roughly 21-mile ride on a 97-degree day on a white Specialized e-bike she’d borrowed from a local shop, it became clear that for her, St. Louis’s seeming sea change isn’t just about the money.

After decades of disinvestment in sustainable mobility, it’s fair to say that the Jones administration is attacking the problems of car dependency on a number of policy fronts, too, developing its first-ever transportation and mobility plan while simultaneously overhauling its land use and zoning plans, too. The Board of Aldermen, meanwhile recently launched a ballot measure to establish the city’s first Department of Transportation, which could pave the way for profound structural change in how St. Louis makes its transportation decisions.

The dust won’t even settle on those foundational shifts before new, bigger projects get pushed forward. The regional light rail network, Metrolink, is in the final stages of planning the first rail route to connect the overwhelmingly Black north side and with the central corridor and the southern half of the city, bridging the infamous Delmar Divide; the Missouri Department of Transportation is even talking about building its first-ever protected bike lane on a state-owned road within the city limits.

That all those things are happening at once might seem like a miracle, or at least like a victory lap for generations of advocates. Like many cities that have faced a sudden infusion of cash and interest in sustainable transportation, though, it also means St. Louis will soon face a test: whether it can keep the momentum going, or fall back on its old ways.

“Hopefully it does not fall back to where it was a decade ago,” said Jacque Knight, a project manager with planning firm CMT who is leading the city’s development of the new transportation and mobility plan. “Because that wasn’t enough to maintain the system we have, let alone to build the things we want to have. I think the level we’re at now is maybe exceeding peer cities — but where we were before was not even reaching parity with [those cities].”

Scott Ogilvie, manager for the city’s Complete Streets program, argues that disparity was more about resources than political will. Now, both are growing.

“It’s not just that [our peer cities] want to do the right thing more than we want to do the right thing,” said Ogilvie. “The building of this stuff is actually pretty complicated, and the maintenance is actually pretty complicated, and we are ultimately limited just by the number of people we can employ to do this stuff. Even if we’re like charting a course to, I think, deliver a more contemporary transportation mobility product, we will still suffer from just being a shrinking Rust Belt, tax-constrained city that has not been able to invest the amount that it should have been investing — that we wish we could have invested — over decades.”

How we got here

Knight and Ogilvie, who also attended the mayor’s ride, have grappled with many of these struggles firsthand over the course of their careers.

Once home to more than 850,000 people in 1950 with a transportation network built to accommodate a projected one million residents, they’ve have watched St. Louis’s tax base shrink to just 301,000 in the last census, bleeding money that could have been used to right-size overbuilt streets in the process.

Today, much of the city’s transportation funds are distributed through a Byzantine process known as the “ward capital system,” where the city’s alderpeople — not transportation experts working off of a data-driven city-wide plan — are often forced to save up their ward funds for years before they can greenlight even the simplest neighborhood bump-outs. Meanwhile, the city staff responsible for managing the design of those projects comprise a tiny crew of around 20 people, and they sometimes find themselves pulled in to other efforts that have nothing to do with keeping roads safe.

“I was in Toronto on a walking tour one time, and the person leading the tour was like, ‘I am one member of Toronto’s 30-person Sidewalk Experience Team,’” laughs Ogilvie. “And I’m like, ‘That’s so great that you have a 30-person Sidewalk Experience Team.’ We don’t.”

Those structural challenges have come into sharp focus as traffic violence has accelerated in the St. Louis region — and as anger among advocates mounted.

That outrage didn’t fully boil over into the public consciousness, though, until St. Louis’s traffic violence crisis began to grab national headlines, including when a driver struck 17-year-old volleyball star Janae Edmonson, causing the loss of both of her legs.

The initial uproar following Edmonson’s crash spurred some calls for increased police enforcement. But St. Louis is also the birthplace of the Black Lives Matter movement, which was was sparked, in part, because of very poor police enforcement. So it’s fitting that some residents openly questioned the traditional fallback on traffic enforcement, pointing out the critical role played by road design. (Edmonson eventually did sue the city for failing to maintain the intersection in a safe condition.)

“Unfortunately, sometimes it takes a major crisis to realize that things have to change,” Knight added. “St. Louis is not unique [when it comes to] the traffic violence issues that are playing out all across the U.S. But I do think that in the past three to five years, some really unfortunate, high-profile traffic fatalities have really made us think about the safety component of a multimodal transportation network.”

‘You have to ride a bike’ to get it

On the mayor’s recent ride, though, it became clear that St. Louis’s safety awakening is as much about joy as it is about outrage — and together, those two forces could be creating a powerful shift in culture.

About half of the riders that day belonged to the city’s quickly growing advocacy community, which swelled in numbers as the COVID-19 pandemic sent hundreds of St. Louisans in search of safe, outdoor ways to have fun with their neighbors, super-charging an already-vibrant group ride culture that has been the lynchpin of the local cycling community for years.

The weekly BICI ride — self-billed as a “casual cycling club for social deviants” — was founded during the quarantine era and soon grew to attract hundreds of riders, a number that rivaled the massive Ghost Ride that rolls on every full moon; Black People Bike began as a similarly casual outdoors club and soon became a full-fledged non-profit, much like the Monthly Cycle, a long-standing group that focuses on women, femme and non-binary people. (Read the name again if you didn’t catch the pun.)

Some of those rides were rowdy parties-on-wheels where riders blast music out of portable speakers and stop mid-route for beer. But on nearly all of them, the revelry had lead to serious advocacy.

“We were just having a lot of conversations with folks about how dangerous it felt to ride on the streets, and how all of us wanted to do something, but it didn’t feel like there was any avenue to do it,” said Dani Adams, one of the co-founders of the newly formed Coalition to Protect Pedestrians and Cyclists. “[We were asking], ‘Where can I make my voice heard?’ … We were just constantly talking about it. We were constantly bitching about it, honestly — about how unsafe the roads are.”

The Coalition might not have formed in direct response to the recent outpouring of city money and policy change, but they certainly took advantage of it.

When St. Louis launched a series of open houses about using American Rescue Plan funds to redesign several major arterials — an effort that came about, in part, because another advocacy group urged the administration not to simply repave those roads without making them safer — the Coalition didn’t just flood the meetings with public comments, but also mounted community engagement rides and walks along each of the routes so advocates and city staff could talk through the proposals in real time.

Local media took notice — and the next time she rode, the mayor invited the advocates along. Jones had toured the city on bike with staffers, but her office is increasingly thinking of group rides and walks as critical tools to engage the community — and to give her fellow officials first-hand experience of what it’s like to move through the roads they govern outside of a car.

“Moving at a slower pace allows us to see the real needs in different parts of our city much more clearly,” the mayor added. “And it’s an enjoyable way to get around St. Louis. For those who haven’t biked here in a while, I encourage you to try it, to see some of the improvements we have already made, and to fall in love with our city all over again.”

Some are hoping the strategy will open eyes not just to the sometimes harsh realities of life behind a set of handlebars, but to how different that perspective can be from neighborhood to neighborhood.

“Windshield bias is a totally real phenomenon,” added Ogilvie. “You’ve got to wait at a bus stop; you’ve got to get on a train; you have to ride a bike around to fully digest why some of these things are really important. Look, I’ve been riding a bike around St Louis since I was a teenager; it’s second nature. But doing it with my daughter is a different experience [and] if I lived in a different part of the city, it would be far more constrained.”

Looking ahead

Of course, the Gateway to the West’s watershed moment isn’t a sure thing.

The new projects still need to be perfected, nevermind actually built. The city will need to contend with a state government that’s investing far more money into widening 250 miles of a single interstate than traffic-calming the dangerous roads within St. Louis that it maintains. The battle to get St. Louis its first Department of Transportation has been mired in political confusion. Even the advocates who have already had such an impact are figuring out how they can sustain their movement without burning out.

And of course, nearly a century of car dependency will be hard to reverse, even with a historic level of money, energy, and policy change coming down the pike. I’ll dig into each of those challenges in the coming days as this series continues.

But on the day of the mayor’s ride, at least, I couldn’t help but take a moment to feel hopeful about what more than $300 million could mean for these beautiful, potholed streets — and how the people who pedaled alongside me might sustain that momentum long after the money has come and gone.

“These aren’t projects we’re trying to sneak in at midnight,” added Ogilvie. “These are projects that people want to highlight and celebrate. They’re a key element of building a city with high quality of life.”