Editor’s note: this article is the second in a series about a pivotal moment in St. Louis’s sustainable transportation evolution, and how it mirrors similar moments in other U.S. cities. Click here to read the entire series

When Jen Wade describes what she does for a living, she says she works for a “maintenance organization.”

It’s a funny thing to say about the Missouri Department of Transportation, which is actively expanding hundreds of miles of interstate in addition to patching potholes and re-striping lanes. In the city of St. Louis, though, where Wade serves as MoDOT’s area engineer, she says the top priority is always upkeep — even if certain “improvements,” like adding bike lanes, have fallen by the wayside.

“When we’ve gotten feedback from our residents, we hear, ‘We need you to take care of the system that we have first,’” she said. “’And then, after that, you can expand or improve.’”

But that may already be changing.

On a recent bike tour of St. Louis hosted by Mayor Tishaura Jones which I attended, Wade told a crowd of staffers and advocates about a slate of safety-focused redesigns coming soon to MoDOT-maintained roads within the Gateway City. Those programs — which are largely funded by federal formula grants and attached to repaving projects — represent a significant chunk of the $300 million of multimodal investment that will be installed in the Missouri community over the next three years, and, some say, a promising evolution of the agency’s relationship with the city.

“It’s typical for cities and state DOTs to have tense relationships,” said Scott Ogilvie, the city’s Complete Streets manager. “But I feel like both city staff and MoDOT staff have really committed themselves to working very closely together over the last several years, and building a strong and open line of communication.”

That evolution may soon push MoDOT towards major new accomplishment: building what Wade suspects is the first protected bike lane the agency has constructed in its 111-year history.

And she says it wouldn’t even be on the table if the city hadn’t committed to its own bike lane-building bonanza first.

“The city kind of forced our hand, because they’re bringing so many cycle tracks to touch this segment of [Missouri Route] 100,” Wade told the onlookers, referring to the stretch of road known locally as the Manchester/Chouteau corridor, where the proposed protected bike lane would be built. “I mean, really, we can ignore it, until there’s five cycle tracks touching my road. Then we really have to find ways to connect them.”

Of course, that’s only one bike lane in a city full of dangerous routes for cyclists, and the plans aren’t finalized just yet. But if they are, it could be an a sign of a new era of collaboration between the city and the agency — and an object lesson for what it takes to get reluctant state DOTs everywhere to venture into vulnerable road user protection.

‘An odd bird’

Wade is well aware that state DOTs don’t always have the best reputation among people who walk, bike, and roll.

A recent Smart Growth America analysis found that 54 percent of pedestrian deaths in urban areas happen on state-owned roads, despite the fact that those roads make up only 20 percent of the total road network. Vision Zero program director Jenn Fox argues that’s because “these roads are more likely to be high-speed, high-volume arterials” than city-owned streets — and she also points out that they’re more likely to “run through communities of color and low-income communities that suffer disproportionately from traffic crashes.”

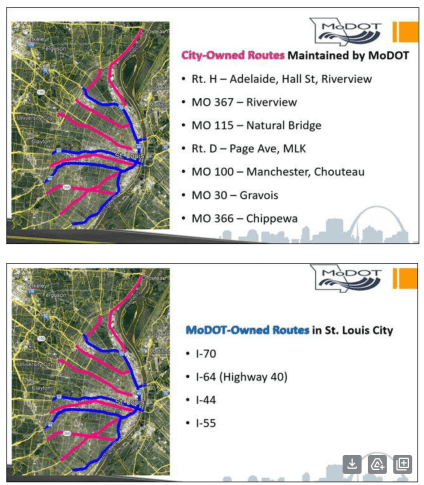

In St. Louis, though, MoDOT doesn’t actually own any roads at all, besides the four whopping interstates carving through the heart of the region — though the agency is responsible for maintaining some of the city’s most dangerous neighborhood routes.

Wade explains that unlike most U.S. municipalities, the Gateway to the West has maintained legal rights to virtually all of the non-freeway streets and roads within its borders, including seven key “legacy” highways that were given traditional street names as neighborhoods grew up around them and pedestrians proliferated.

A few decades ago, though, Wade says MoDOT entered into an “odd bird” agreement, where the agency would handle most of the curb-to-curb upkeep along those seven routes — think patching potholes, replacing signals, and re-painting faded road markings — even as the city maintained its rights and responsibilities over things like sidewalks and lighting, as well as key decisions about on-street parking and curb cuts.

At the time, the move seemed like a win-win for St. Louis taxpayers, who had been paying into MoDOT’s coffers without receiving the same maintenance benefits granted to Missourians just a little further down those seven roads, since all of the routes under the maintenance agreement extend well beyond the city’s borders.

When residents push to redesign those roads for safety, though, they often have to navigate between two government entities with wildly different standards, practices, and funding streams, and it’s not always clear to laymen who’s leading. While the city technically owns the roads, it has to secure MoDOT’s approval to redesign anything beyond the sidewalk, and the city typically has to fund those safety changes itself; MoDOT, meanwhile, is often hesitant to approve those redesigns if it will complicate its resurfacing plans, which are crafted years in advance.

“For example, we’ve got [an alderperson] who wants to put a bump-out on Gravois,” said Wade, referring to notorious arterial that runs diagonally through the southern half of the city and ranked as the third-deadliest route for pedestrians in St. Louis last year. “Which is great; it’s going to help. We are going to approve it, and they are going to fund it. But I’m coming back in 2030 and I’m going to pave this.”

In the Gravois example, Wade hopes MoDOT will actually incorporate more traffic-calming features along the corridor when it’s time to resurface the route, rather than simply tearing out the bump-outs to make the asphalt easier to replace. When it comes to novel infrastructure like protected bike lanes, though, the agency has historically been hesitant to approve new projects it didn’t seem like the state or the city could adequately maintain – especially since neither owns an appropriately sized sweeper or snowplow, and neither can justify the cost of that equipment for just a handful of routes.

Bike Portland recently priced a single bike-lane sweeper at between $283,000 and $345,000, and hiring a crew to run it can be costly, too.

“It’s like, ‘OK, are we supposed to buy four machines and staff up to be sweeping [the bike lane] on a weekly basis or a biweekly basis?'” she asks. “We’re not doing anything even close to that on the rest of our route. … And without an entire network of [protected bike lanes] to have to take care of, where is impetus to purchase that machine?”

With tens of millions of dollars of bike lanes coming to St. Louis roads, the price of a bike lane sweeper might seem a lot more reasonable soon.

Wade says that the sheer scale of the city’s bike lane investments has pushed MoDOT to accept a tentative “verbal agreement” that will obligate the city to maintain any Manchester-Chouteau bike lane the state builds, which was critical in empowering them to move forward with the project. Formalizing that agreement could be essential to keep the momentum going for future projects.

“In this case, the city moved ahead of us,” she added. “They are not only building a protected bike lane somewhere; they are building many of them. … It’s not wishful thinking. It’s not just written somewhere in a plan. They are in design; they are funded. Some of them have already been built. They are coming to touch Chouteau — and when you look at a map of the region, there aren’t other options [for bikers to travel safely nearby].”

Keeping the momentum going

Simply building a ton of city-funded bike infrastructure, though, won’t always be enough to goad state transportation agencies to do their part to fill in the gaps.

To get MoDOT to keep building bike lanes and other traffic calming infrastructure, Wade says it’s helpful if advocates keep up with the agency’s Statewide Transportation Improvement Program, which details which roads the agency is scheduled to repave over the next four years, and represents an ideal time to push for new safety improvements while the construction crews are already on site.

Most of the American Rescue Plan-funded street safety redesigns that the city is doing now came out of what were originally intended to be simple repaving projects, before advocates pushed for more.

And when safety just can’t wait that long, the politicians may need to get involved.

Wade explains that when MoDOT does more than maintain the roads it already has, it’s often because the state elected officials have championed a certain project and secured taxpayer funding for it in the legislature — like Gov. Mike Parson’s controversial pet project along Interstate 70, which will add a lane to a whopping 200 miles of highway.

“The funding on I-70 for the expansion, the addition of lanes, is not coming from a road use fund — it’s coming from general revenue,” she added. “So the legislators decided that I-70 needs to be expanded, and they funded it to the tune of $2.8 billion. They handed us a huge chunk of change and said, ‘This is our legislative priority. Get this done.’ That puts a huge onus on our organization, but it is completely separate from, and on top of, the funding we have been given to manage.”

If advocates can push policymakers to pass similar bills promising funding for multimodal projects, though, it would place the responsibility on MoDOT to bump those efforts to the top of the queue — especially if they’re are already on the agency’s list of High Priority Unfunded Needs, which includes a cool $100 million a year in multimodal projects.

Perhaps most important, Wade encourages advocates to recognize how quickly culture is changing among state transportation leaders, and take advantage of that shift while it’s happening. She credits U.S. DOT for committing the country to a Safe Systems approach for the first time in history, and for developing new resources that not only support but encourage state DOTs to build safer infrastructure — and gives them easily usable tools to help sell the public on those changes.

Today, that might be a single protected bike lane along a single Missouri road. Tomorrow, though, those ambitions might be far bigger.

“The field of transportation engineering is learning a lot about how to create safety,” Wade says. “[The Federal Highway Administration] seems to be leading the way in this; [they’re] really opening up to more opportunities for looking at road diets, looking at alternative intersections, talking about all those proven safety countermeasures, and really trying to encourage them. … The industry, I think, is moving in the right direction.”

Of course, the details of how the state and the city will implement those countermeasures matter — and in St. Louis, local advocates are fighting to make sure they get it right. I’ll explore how they’re doing that in the final installment of this series.