Well here we are — the beginning of the age of congestion pricing.

It finally happened after literal decades as a mere idea: One failed push in the aughts by then-Mayor Mike Bloomberg then a successful push in the 2010s by environmental and transit advocates with an eventual assist from former Gov. Andrew Cuomo, who now more than anything wants you to forget that he was the guy who twisted arms in Albany to get it done.

If you’re a driver, and you’re looking for a villain outside of the mirror in your bathroom, it’s Cuomo, a well-known terrible guy. If you’re a transit rider, pedestrian, cyclist or even driver excited about this new era in New York City, you should be happy that congestion pricing, with all its benefits, outlasted the disgraced ex-governor, who’s spent the last year trying to gaslight voters into forgetting that he was the governor who twisted arms in Albany to get it done in the first place.

Congestion pricing even survived the rollercoaster ride of Cuomo’s successor Gov. Hochul, who first wholeheartedly embraced the toll, then chickened out in the most asinine way, and then decided to bring it back, albeit at a lower price point. It’s also survived multiple court challenges built on a twisted notion that the Constitution guarantees the right to drive a car for free into the most congested and transit-rich area in the United States. (Reminder: tolls exist!)

But here we are! We made it!

So when exactly did it start?

Exactly at 12:00:01 a.m.

Remind me, what are all — literally all — the fees and times?

Strap in, because there are a whole bunch of numbers for you:

At the most basic level, the toll to drive into the area of Manhattan below 60th Street has a peak period from 5 a.m. to 9 p.m. Monday through Friday, and 9 a.m. to 9 p.m. on Saturday and Sunday. The remaining hours are considered the “overnight” period.

Now let’s go over all the current costs (keeping in mind that all the fees below will rise 33 percent in 2028 and then another 25 percent in 2031):

- Regular passenger vehicles: $9 (peak) and $2.25 (off-peak). One charge per day, no matter how many times a driver enters and leaves and returns.

- Small trucks and charter buses: $14.40 (peak) and $3.60 (off-peak).

- Tractor trailers: $21.60 (peak) and $5.40 (off-peak). Unlike cars, both classes of commercial trucks are charged each time they drive into the CBD.

- Intercity commuter buses on fixed schedules and yellow school buses with city contracts to transport students are exempt from the toll: No toll at all.

- Tour buses: $21.60 (peak) and $5.40 (off-peak).

- Motorcycles: $4.50 (peak) and $1.05 (off-peak).

- Yellow or green cab passengers: 75 cents per trip.

- Uber/Lyft passengers: $1.50 per trip.

Here’s what that looks like in one handy MTA chart:

But those are just the E-Z Pass numbers. Isn’t there another way to pay?

If a driver does not have E-Z Pass, the tolls are roughly 50 percent higher, and the bill will be mailed to you.

That, of course, is the theory, but as anyone familiar with traffic enforcement cameras knows, tens of thousands of incidents of speeding or red-light running are never punished because the camera cannot read the plate or because the plate itself is fake and therefore not registered to the car owner’s home.

The city Department of Transportation logs the numbers of unreadable plates, and data expert Jehiah Czebotar visualizes them every quarter on his website. The takeaway? Two out of every nine recorded speed violations in New York City were rejected in September 2024 (the most-recent month for which there is data) because the vehicle had a temporary license plate, a marred or otherwise unreadable license plate, or no detected license plate at all.

The city data show that the biggest offenders are motorcyclists or moped riders who do not have the required plates. Those motorists are subject to a small congestion fee.

Most alarming are the tens of thousands of speeding incidents that were unticketable because the driver had a temporary plate. The city DOT can’t access address information for legitimate out-of-state temp tags, nor can it (obviously) issue a ticket to a driver with a fake tag because the entire point of illegally buying a fake temp is to avoid accountability.

The MTA, because it has a police force, has access to state DMV data for legitimate temporary tags, and says it is only 1.5 percent of its toll transactions are unbillable. But a spokesman confirmed late on Saturday that “there are some states we do not receive temp plate information from.” (The agency said it would provide the list on Monday.)

And the agency’s congestion pricing cameras will not be able to ticket drivers with fake temps. The agency is part of an NYPD, State Police, DOT and other agency task force to apprehend those drivers.

Here’s what Czebotar’s chart looks like:

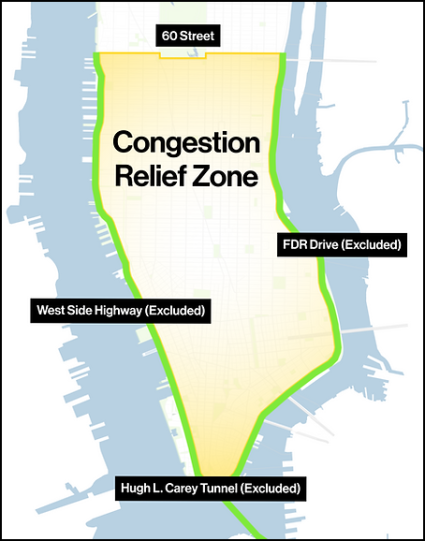

Where do drivers pay the toll?

Whenever a person drives south of 60th Street in Manhattan, a toll camera will record the trip. But there are some exceptions: If you’re driving into Manhattan over the Queensboro Bridge, you won’t pay if you exit the bridge directly onto E. 62nd Street and then you continue your trip uptown.

Drivers also won’t pay if their entire trip is inside the CBD, or if the enter the zone on the West Side Highway or the FDR Drive and do not leave that roadway to access, say, the Brooklyn Battery Tunnel (or vice-versa).

Additionally, last year the MTA told the Tribeca Citizen that drivers going from Battery Park City to other destinations inside the CBD won’t be charged, even though they will cross the West Side Highway. (Of course, residents of Battery Park City, like all residents of Manhattan south of 60th Street, will be charged when they leave the highway.

And there are credits for some drivers entering via already-tolled bridges and tunnels, right?

Yes, and this is the crazy thing if you’ve been following New Jersey’s opposition to congestion pricing. Their drivers — who tend to be wealthier than the area average income — won’t even pay that much.

If you drive a car into Manhattan during the peak toll period through the Lincoln Tunnel or Holland Tunnel, you get a $3 toll credit — meaning you only pay $6 more than the non-controversial toll you are already paying.

Drivers who enter through the Queens-Midtown Tunnel or the Brooklyn-Battery Tunnel you get a $1.50 credit, while motorcycle riders get credits of $1.50 and 75 cents. Those credits will rise in tandem with the increases in the tolls set for 2028 and 2031.

Small trucks and buses get a credit of $7.20 if they enter via the Lincoln Tunnel or Holland Tunnel and $3.60 for the Queens-Midtown or Brooklyn Battery.

Large trucks and sightseeing buses get a $12 credit through the Lincoln and Holland tunnels and a $6 credit for the Queens-Midtown and Brooklyn-Battery tunnels.

The $9 peak toll sounds really low. If the toll really did reflect the damage that drivers cause to our city in the form of productivity-destroying congestion, lung-harming pollution, safety-depriving crashes and the economic cost of reduced quality of life, shouldn’t the fee be higher?

Look, a first-in-the-nation toll like this needs to play in reality and not just on spreadsheets and theory (no offense to the makers of spreadsheets and theories). To actually implement a controversial policy — and polls indeed show that congestion pricing is not popular — politicians chose to make the price palatable to the general population and within the tiny box of political courage that they rarely ever open. So that means, even if the correct price of the toll should be $80, politicians must put aside what is technically right in order to achieve the possible. Hell, even economist Charles Komanoff, who found that every car trip into lower Manhattan costs other drivers $100, was OK with the $15 toll that will be levied on drivers by 2031.

OK, so at $9, tell me everything great about congestion pricing — like how much traffic it will reduce, how much money it will raise for transit. You know, everything.

Even at $9, congestion pricing will do plenty of great stuff: the toll is expected to reduce the number of vehicle miles traveled in the Manhattan central business district by 6.4 percent, and reduce the number of vehicles driving into the CBD by 13.4 percent. That’s not as much as the projections for the $15 toll (8.9 percent fewer VMTs and 17.3 percent fewer vehicles) but it’s not nothing.

Fewer vehicles in Manhattan means better air quality, faster buses and fewer crashes in one of the most congested areas of the entire country, and it also means more opportunity for the city DOT to build more bike lanes, bus lanes and pedestrian space in the most transit-rich and densest area of the country.

The lower toll will also still be able to meet the original congestion pricing law’s central requirement: that the toll raise enough money for the MTA to borrow $15 billion for projects in the 2020-2024 capital plan.

And what about working people living in the zone?

People who live in the CBD and make less than $60,000 are eligible for a tax credit from New York State that will cover all of the congestion pricing tolls accrued by that driver.

Additionally, drivers making less than $50,000 per year can register their vehicle with the MTA to get a 50-percent discount on the peak toll for every trip into lower Manhattan each month after the 10th full-fare toll.

Also, disabled New Yorkers can get a full exemption from the toll by registering a vehicle with the MTA that they or a family member or caretaker will use to drive them.

But isn’t this going to turn the areas just outside the zone into parking lots?

No. The congestion pricing environmental assessment found that areas in Queens, Brooklyn and Manhattan just outside the CBD would also enjoy reductions in VMT and total vehicles. That projection matches the reality of how congestion pricing has played out in other cities, where neighborhoods just outside the toll zones did not become full of people trying to park before finishing their commutes on public transit.

The federal government and congestion pricing experts are split on the question of what will happen further from the CBD. The EA found that regionally, there will be a tiny drop in VMTs on roads in the full 28 county region from Connecticut to southern New Jersey — 0.5-percent max.

But Komanoff’s model, a surgical instrument compared to the blunter tool used by the MTA according to “Gridlock” Sam Schwartz, found that under the approved congestion pricing scenarios there would be a 2-percent drop in daily VMTs outside lower Manhattan, amounting to two million fewer VMTs in the entire region.

And what about all those complaints from theater owners, restaurateurs and businesspeople who think this is going to be bad for them?

Ah yes, we must save our Neil Diamond jukebox musicals. The thing about huge traffic jams is that they also cost money. The Partnership for New York City, hardly a bastion of progressive thought, has consistently supported congestion pricing because time is money and the time lost to pointless traffic jams in Manhattan costs in the neighborhood of $20 billion per year.

Leaving that aside, the overwhelming majority of people coming into lower Manhattan get there via public transportation — the MTA says it’s 90 percent of work commuters, for example. And even non-commuters, such as Broadway lovers, restaurant patrons and people who want to buy stuff they might not even need, rely mostly on transit.

People who insist on driving into the city to see a show or have a meal will benefit from less time being stuck in traffic.

And consider that according to the Broadway League, the vast majority of theatergoers are either from New York City or visiting from outside the region or from other countries — very few of whom drive around the city.

In the end, only 15.6 percent of Broadway-goers drove their own car to the theater whereas 76.2 percent of the audience walks or uses transit.

In addition, the average household income of a suburbanite who goes to Broadway is $294,000. “Twenty-eight percent of the audience reported an

average annual household income of $250,000 or above, compared to

7 percent of the U.S. population,” the Broadway League said in its most-recent demographic report (which we had to pay for!).

The average ticket price for a show is $161.20, meaning if four New Jersey residents get in a car to see a show, the additional $6 congestion toll they’ll pay represents 0.9 percent of their theater costs, before even calculating in food, parking, souvenirs and maybe a post-show drink at Sardi’s.

But we’re sure theater-goers know all that, given the Broadway League’s boast that “Broadway theatregoers attained higher levels of education than the United States public in general.”

Didn’t the hospitals on the East Side of Manhattan complain?

Oh, man, this was really rich! Just after Gov. Hochul restored congestion pricing, two officials from NYU Langone Health — Nancy Sanchez, the executive vice president and vice dean for Human Resources, and Executive Vice President Elizabeth Goldstein — wrote a letter to all hospital employees telling them that while the hospital “recognizes the environmental and infrastructure goals behind congestion,” it objects to the toll because it “will hurt vulnerable patients and the healthcare workers.”

The letter also claimed, without evidence, that “the vast majority of patients travel to us from outside the zone” and that the hospital employ “over 20,000 individuals who travel into the zone for work.”

We reached out to the hospital for more information, but none was provided. The wording of the second part of that sentence — “over 20,000 individuals who travel into the zone for work” — is meaningless, given that most of those individuals take transit to get there and would therefore not pay any toll.

It’s also worth nothing that Sanchez is hardly a figure who should be complaining about a transit-boosting toll on behalf of her struggling workers: In 2023, she earned $2.37 million in salary, according to Crain’s New York Business Health Pulse Extra.

The other signer of the letter, Elizabeth Golden, is a former Pfizer executive. She was hired in 2023, so it’s unclear what she makes, but her predecessor, Kathy Lewis-Epstein, earned $3.82 million in 2021.

It’s likely that their letter did not come as a result of action by the NYU Langone board or high level staffers. For instance, Quemuel Arroyo, who is the MTA’s Chief Accessibility Officer (and supports congestion pricing), is on the NYU Board. And MTA Board member John-Ross Rizzo is an NYU Langone doctor (who also supports congestion pricing). And a former MTA Chairman, Joe Lhota, is an executive vice president, a vice dean, the chief financial officer and chief of staff at NYU Langone.

We reached out to the MTA for comment on the letter.

“We don’t have a choice but to deal with horrible traffic congestion because people in ambulances are stuck in traffic and in some cases dying,” said spokesman Aaron Donovan. “If NYU’s richly compensated executives are truly interested in cutting costs for drivers, they could start with their parking rates, which currently stand at $15 for 30 minutes.”

Shouldn’t we have sympathy to drivers who complain?

No, we shouldn’t. The vast majority of people who get into the central business district use transit — and those who drive are, on average, wealthier than their transit-using neighbors.

And the suburbanites who are whining the loudest are far wealthier than city residents who drive:

As Streetsblog has exhaustively covered, a Long Island or northern suburban car commuter into the central business district has a median income of roughly $169,000 per year, and a Garden Stater who drives in to work has a median income of $141,000 per year.

Meanwhile, median income for people who take transit to their job south of 60th Street is $114,000 — or 32 percent less that the median Long Islander.

And the congestion pricing environmental assessment found that only 13.7 percent of education, healthcare and social assistance employees drive to work in Manhattan (many of them to jobs outside the tolling zone anyway). Plus, employees driving into lower Manhattan between 9 p.m. and 5 a.m. would pay only the $2.25 overnight toll.

And, lest we forget, when Gov. Hochul lowered the proposed toll from $15 to $9, she did not also provide a 40-percent cut in the cost of Long Island Rail Road or Metro-North fares, which means that a train rider from Hicksville will pay significantly more than a driver from Hicksville, which makes a mockery of Gov. Hochul’s claim that she is a climate champion.

So congestion pricing will raise how much revenue? Which can be bonded to what?

The MTA was required by law to create a toll that would allow the agency to raise enough money to bond out to $15 billion for the 2020-2024 capital plan, which was the most ambitious effort to update the system in decades. While it was initially believed it would take $1 billion per year to do that, when the $15 toll was approved by the federal government the MTA said that the economic environment (you know, interest rates and stuff bankers and bond sales people say to each other) meant that the agency could make do with $900 million in toll revenue per year.

The $9 toll is projected by the MTA to raise $500 million per year, but because it’s set to go up over a six year period and because interest rates are still high, the MTA still believes it can use the toll to backstop the borrowing, and the federal government believes the MTA on that one.

But how long will that take to pay back?

Lol no one knows for sure. But we do know that since the money will come in more slowly with a $9 toll instead of a $15 toll, it will slow down the completion of some of the projects it’s supposed to pay for.

And this will create revenue for all the future capital plans, right? We’re set for life?

No, and this is something that very few people realize — and the ones who don’t realize it because they weren’t paying attention will likely scream when they learn: congestion pricing is only underwriting the MTA’s borrowing for the 2020-24 capital plan, not future capital plans (at least until the current five-year reconstruction program is paid off).

But congestion pricing is so important because it’s exactly the new, dedicated revenue that no less an authority than state Comptroller Tom DiNapoli has been talking about for years. Using money from congestion pricing takes the pressure off the agency’s otherwise extremely tight debt situation.

In the world of big money borrowing, congestion pricing is a totally separate and new revenue stream from the MTA’s normal fare- and toll-backed revenues that the agency has used to pay off its bonds. Congestion pricing is that rarest of things in politics: a reliable revenue stream.

What about all the pollution I’m hearing about in The Bronx and in Jersey? How does a toll that reduces driving and vehicles end up increasing pollution in some places?

Yes, the congestion pricing environmental assessment predicted that there will be shifts in driver behavior that results in some drivers choosing — especially truck drivers — to drive around rather than through Manhattan. Such a shift, could mean increased truck traffic on the Cross Bronx Expressway and George Washington Bridge, I-278 in Staten Island and on the Lower East Side near the FDR.

Those increases in pollution are the basis of many of the failed lawsuits against congestion pricing. Why did they fail? Partly because none of the modeling found that any emissions would violate standards set by the National Ambient Air Quality Standards.

Our air will get a tiny bit dirtier in several isolated areas in a 28-county region, but not nearly dirty enough to violate the law.

Plus the MTA is mitigating the pollution, right?

Yes, in the Bronx the MTA has promised to pay for electric truck charging equipment and electric refrigeration trucks at the Hunts Point Market to replace the diesel-spewing refrigerator trucks that are currently used to store food at the warehouse hub. In other areas that could see reduced air quality, the MTA has promised to pay for things like more roadside vegetation and air filtration systems for schools near highways, as well as park and green space upgrades.

The MTA has laid out the specific neighborhoods in New York and New Jersey that are going to be given specific dollar amounts for its place-based mitigation efforts, with a funding formula based on the population that could be affected by air quality impacts. An attorney for the MTA even said in court on Friday that the agency had begun talking to New Jersey communities about what kind of projects would work as mitigation measures.

And wasn’t there this awesome feature that the MTA could raise the fee on gridlock alert days. That sounds really smart, right?

It is smart and interesting to allow the MTA to actually add some teeth to the city’s occasional Gridlock Alert Day by raising the peak toll by up to 25 percent, so the DOT doesn’t have to just impotently beg drivers to pwetty pwease use public transit on the days with the most mind-numbing traffic on Earth.

However, Gov. Hochul bowed to the wishes of her boss, Australian (now American) reactionary Rupert Murdoch, and prompted by coverage in the Post (one year after our coverage of the very same tool) vowed to not let the MTA actually use that power once congestion pricing is live.

Sure, congestion pricing is finally up and running now, but aren’t there still threats?

Of course! The Town of Hempstead is suing the MTA on a claim that the agency violated the State Administrative Procedures Act when it announced the congestion pricing toll rates, and that the governor illegally usurped legislative power by pausing congestion pricing and announcing a new lower toll.

The town asked for a temporary injunction to stop the toll, and a hearing on the matter is scheduled for Jan. 16.

And doesn’t a new president get sworn in on Jan. 20? Could he do anything?

In theory, not really. The federal government has already issued a Finding of No Significant Impact. At that point, the feds usually leave it up to the state or city to just do the project.

“I don’t think there’s a lot of precedent for political hostage-taking and presidential involvement in it,” Justin Balik, a former state transportation official, told Streetsblog in November.

In addition, once the MTA begins borrowing off the congestion pricing revenues, that creates a contract with the bond holders — one of the truly inviolable documents in the world. These people have rights to their money, more rights than even you, a regular schmuck, and courts have constantly said so over the course of this country’s illustrious history.

This is also a reason why people believe that if the toll actually starts, it won’t be nuked by a judge.

That said, the law is only as good as the people who hold it up and the people who feel bound by it. Does that sound like Donald Trump to you?

There is a chance that the 47th President might try to revoke the FONSI. Or maybe he tries to end the toll by doing something less explicitly illegal like withholding federal funding New York needs or slowing down the federal approval process for a different program New York State is trying to do.

If you think he cares if a bunch of bondholders sue the MTA into even worse debt servitude than it’s already in, we’ve got a bridge to sell you.

How will we know if it’s even working?

It will of course take time to figure it out, even if some TV news station sends a reporter out there to gravely intone, “Hmm looks like there’s still cars out here” and interview a driver who says, “I don’t go any faster.”

But the agreement that the MTA signed with the federal government to get permission to do congestion pricing also mandates that a host of data is collected and made public. Allow me to simply quote from the agreement, called the Value Pricing Pilot Program:

The program will be collecting a significant amount of data to assess, track, and trend the direct and indirect effects of the project. These data, which are described in the following bullets, will be made public on a regular basis in open data format to the greatest extent practicable.

Direct Congestion Measures

- Vehicle entries into the CBD (by type of vehicle, day of week, time of day)

- Historic volumes entering the CBD (average fall weekday/weekend, time of day)

- Taxi and for-hire-vehicle trips to, from, and within the CBD

- Taxi and FHV VMT within the CBD

Indirect Congestion Measures

- System-wide transit ridership for transit services providing CBD-related service (monthly total ridership by mode and transit operator)

- Metropolitan Transportation Authority bus speeds within the CBD

- Capital projects funded or financed through Project revenue

Monitored and Modeled Air Quality Measures

- PM2.5

- Nitrogen Oxides

- Ozone: via modeling

- Greenhouse gses

Reporting on revenue and for audit purposes

- Project revenue

- Project capital and operating expenses

Also, City Comptroller Brad Lander sent a letter to the MTA and the city DOT demanding that they publish the exact things they’re required to publish, so if we don’t see any data, at some point someone — including someone here at Streetsblog — is going to start caterwauling.

And let’s be honest: Drivers (who are paying) will never think it’s working because they always complain about traffic anyway and they never ride transit, which may actually improve. So what should we say to drivers?

First, drivers do deserve some sympathy. Their lives are miserable because driving is awful (mostly because of all of the drivers who congest the streets for the other drivers). They have been conditioned by 110 years of messaging by automakers and their political enablers that buying a car will give them freedom, but that freedom ends up to be a lie because a car is expensive for the owner and encourages a series of choices (such as to live further and further away from one’s job or family) that end up costing even more and cause more stress.

Studies have long showed that drivers are simply unhappier than non-drivers.

But, dear readers, it’s your journey, so it’s your choice if you want to even engage with drivers at this point. They’ll always complain or pretend they never had a say over the toll when, in fact, we’ve been talking about this version of congestion pricing since 2017, when the MTA launched a very public two-year campaign to get this program approved in Albany.

The facts are out there — in fact, those facts form the basis of this very blog post. We’ve now given you the tools to reason with people who argue that they simply must drive into a congested place that is also the region of the country best served by transit.

So you can use the facts in this story, or just tell drivers to simply screw themselves and the car they drove in on.

— Additional reporting by Gersh Kuntzman