Transportation officials need a radically new framework for understanding the mobility needs of women and caregivers in our cities – and a good place to start is reimagining the “mobility hubs” where so many of their journeys begin, a provocative new report argues.

A team of Swedish and American designers recently released a slide deck for transportation officials to copy and use in community engagement sessions, to help them better understand the “unspoken” travel needs of the women and caregivers they serve. And in an accompanying report, the designers also discuss how cities can translate those insights into betteer places to catch a bus, wait for a train, rent a shared bike, and anything else gender-marginalized people need to get around.

The “mobility hub” — or a central location where travelers can connect with multiple shared modes — is a buzzy transportation planning concept that’s been inspiring articles and studies for years. But the team behind the tool said it couldn’t find any resources about how these spaces could better support women and caregivers, even after poring over all available research on the topic.

And when designers followed that literature review up with workshops with real women, caregivers, and the transportation and planning leaders who shape the networks they use, they discovered a universe of invisible needs that weren’t accounted for in other research.

“We wanted to know: who are these hubs really serving?” said Hannah Wilson, senior director of partnerships and engagement at the Shared Use Mobility Center, which created the framework with Sweden’s Living Cities and Communities. “Who are they not serving? Where are they typically placed, and where are they enabling people to travel?”

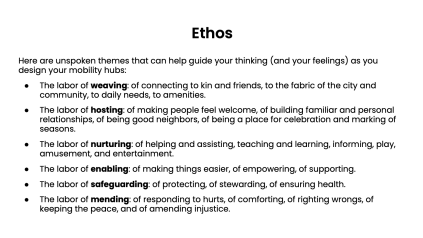

Wilson explains that contrary to popular planning wisdom, women don’t just make shorter and more frequent “chained” trips than their male counterparts, who are more likely to commute to the kind of nine-to-five jobs around which America’s hub-and-spoke transit networks were historically designed. They also perform a raft of invisible labors that aren’t reflected on typical travel surveys, which tend to focus on destinations, distances, and time spent in transit, rather than the underlying reasons why people move — and the largely uncompensated work they need to perform along the way.

Many of the interviewees, for instance, reported spending a lot of time performing the “labor of nurture” for children and other people they love — a burden that might be alleviated by, say, putting a playspace next to the bus stop. Others reported spending energy on the “labor of weaving,” or “connecting to kin and friends, to the fabric of the city and community, to daily needs, to amenities” — a task that might get harder if they can’t use free public WiFI to send a text to grandma while they’re waiting for the train, or if they don’t feel safe interacting with neighbors on an unlit platform.

If designers think creatively, mobility hubs can help alleviate the burden of other forms of unseen labor, too, like helping caregivers perform the “labor of hosting” by popping up a holiday market stall on the sidewalk right next to the bikeshare stand, saving them a lengthy trip to buy gifts. But first, they have to actually talk to the real women and caregivers in their communities, rather than assuming which interventions will best meet their needs.

“It’s not just [about] thinking about the trip destination, or even the categories of places that we go and things that we need to do in our day,” added Wilson. “It’s about stripping that back and thinking about the unseen — and typically, unacknowledged — emotional labor that comes with those trips and with those jobs. … It’s not just checking a box; it’s about helping designers think a little bit more deeply about these unspoken themes and feelings.”

To think even further beyond the checklist, Wilson and her co-designers created a series of composite portraits of their interviewees, complete with names, illustrations, and sets of questions that this person’s experiences might prompt a smart designer to ask. She hopes designers will use them to have a deeper conversation with the riders they serve, who might see a little of themselves in those fictional characters.

“When we talk about mobility hubs, we often talk about the things that you need there — the material things — rather than thinking about the actual needs of the people that they’re serving,” Wilson added. “The development of the personas steered that work and helped us visualize people [who use mobility hubs] and keep them centered. It’s a little bit more of a diagnostic tool, versus a prescriptive tool.”

However they use the framework, Wilson hopes that it will prompt better questions about what it means to design a city for everyone — and ultimately, a better transportation network on the whole.

“Mobility hubs ended up being this lens [through which] we could share broader ideas,” she added.

The Shared Use Mobility Center will host a webinar on this framework on Wednesday, March 6 at 11 a.m. central. Register here.