Diversification is touted as the only free lunch in investing, and so it goes that geographical diversification should benefit investors. Yet international stocks have not rewarded anyone for their patience in recent decades. It’s only worsened: Both developed- and emerging-markets stocks have consistently trailed their US counterparts since the 2010s. Many US investors have cut back on their stake in international markets, especially in the face of soaring US equities performance. But could there still be a case for international diversification?

This Time Won’t Be Different

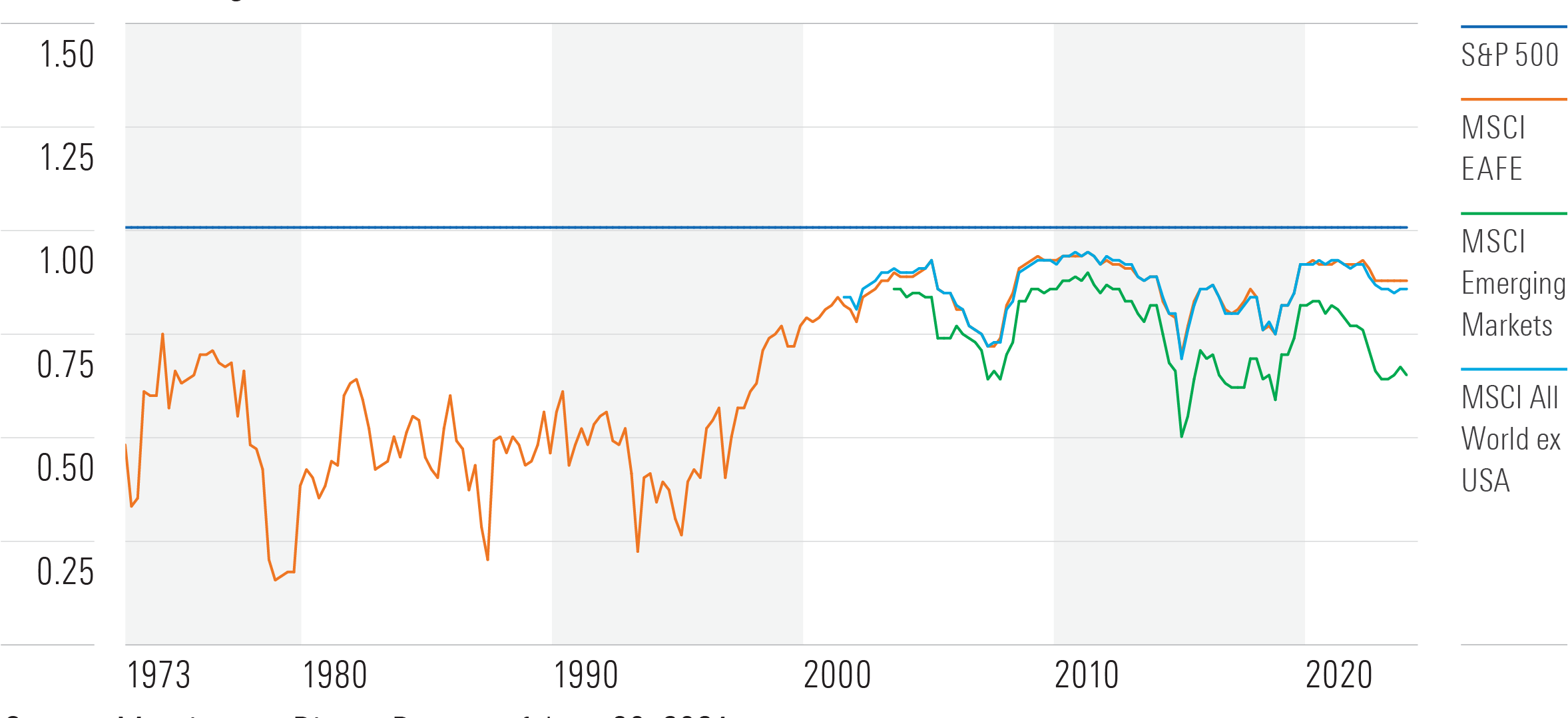

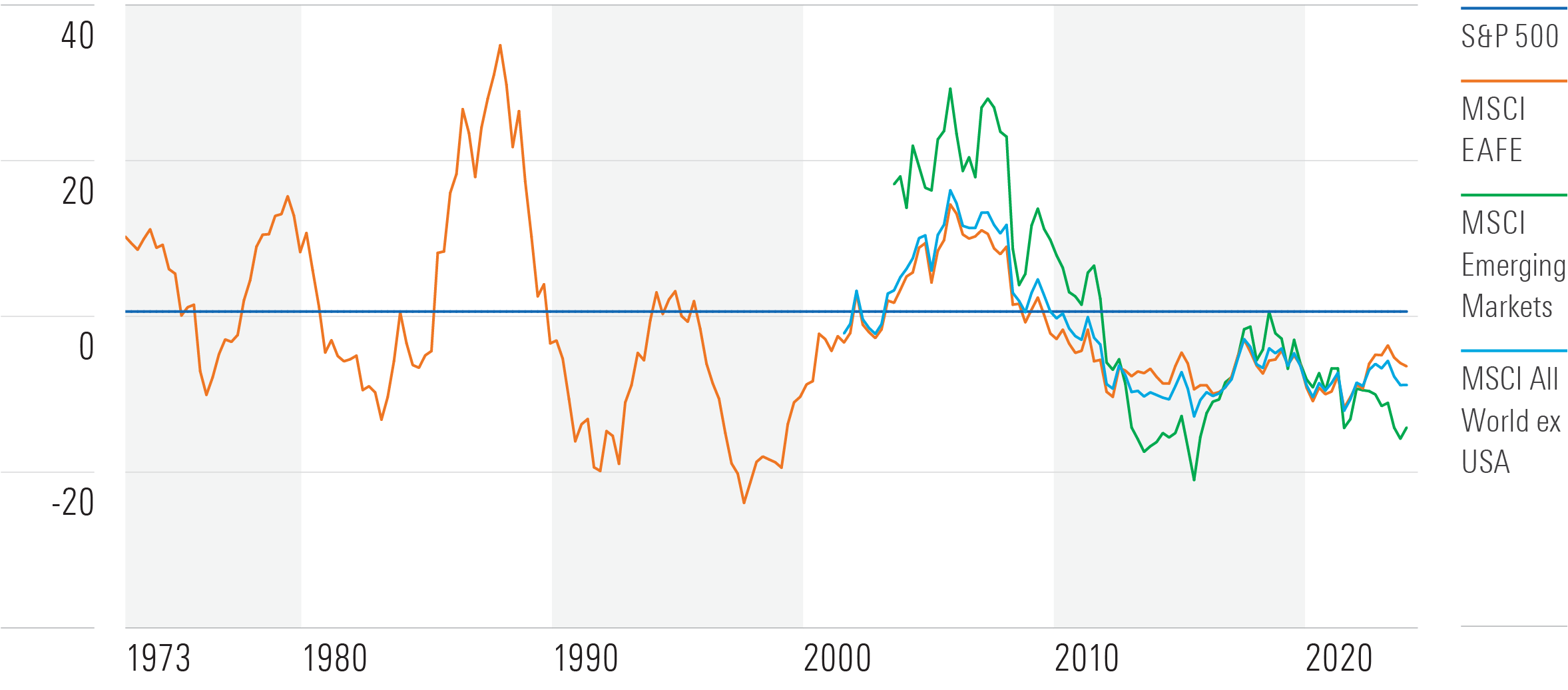

If we’re looking only at recent decades, the answer seems to be a definitive no. Even setting aside performance, the diversification benefit of international stocks seems to be fading for US investors. International stocks’ correlation to US equities has seemingly settled near a new high since the early 2000s, especially for developed markets. But going further down memory lane, this hasn’t always been the case. Exhibits 1 and 2 display the rolling three-year correlation and excess returns of the MSCI EAFE, MSCI All World ex USA, and MSCI Emerging Markets indexes against the S&P 500.

International stocks’ relationship to US equities moves in cycles. While developed markets reacted more in lockstep with the US market now compared with the 1970s or 1980s, the two markets still diverged during stress markets. For instance, in the 2008 global financial crisis, the correlation of developed-markets stocks to US stocks decreased as they outpaced their US counterparts. The same goes for emerging-markets stocks. They outpaced US stocks for most of the 2000s and maintained a correlation of around 0.7, albeit with higher volatility.

Given US stocks’ persistent rise in recent years, it might have been easy to forget how home bias detracts from a portfolio’s diversification. But let’s not forget the US stock market started the 2000s with the dot-com bubble and ended it with the 2008 financial crisis. Investors betting on stellar US stock performance to continue from the 1990s into the 2000s would have missed out on great companies outside the US, plus conversion gains from a weak dollar. Many developed European economies also suffered, but a well-diversified portfolio would have sailed ahead of a US-only one thanks to stakes in Chinese and South Korean stocks, for instance.

Even if history were not to repeat itself, company domiciles are decreasingly relevant in today’s globalized world. The large companies driving today’s stock markets are multinational conglomerates with global business and revenues. A domestic-only portfolio would likely exclude American depositary receipt listings such as $500 billion Novo Nordisk and $200 billion AstraZeneca, both of which derive more than half their annual revenues from the US market. Some of the largest companies in the world such as Samsung Electronics or Saudi Aramco don’t even offer ADRs or trade on American exchanges at all. As with most international stocks, the easiest way for retail investors to access these companies would be via an exchange-traded fund or mutual fund that can handle withholding taxes and other operational hassles on their behalf.

Globalize Your Portfolio

Investors face three main options when choosing an international stock fund: They can 1) build their own portfolio of international stocks using single-country or regional ETFs, 2) outsource the task to an active manager, or 3) go with a broad index fund.

For the first approach, the cost of holding multiple single-country ETFs (which tend to be pricier than broader index funds) and trading in and out of them will be significant. Even if they successfully bet on the right countries or regions, a narrower scope will bump up the portfolio’s volatility and require steadfast discipline to harvest its benefit. Between the added sticker cost and time and effort involved, this method doesn’t seem sensible.

Finding good active managers is possible but can be tricky. Only a fourth of active funds in the foreign large-blend Morningstar Category managed to survive and beat their passive counterparts over the trailing 10 years ended 2023. While this is better than their active domestic funds counterparts, the odds are hardly convincing. Investors can look to active, yet systematic, strategies that limit manager discretion risk while still enjoying flexibility to add marginal improvements over broad index funds, such as Dimensional International Core Equity Market ETF DFAI, which earns a Morningstar Medalist Rating of Gold as of November 2023. The fund leans toward value and small-cap names with higher upside potential, while its profitability tilt weeds out struggling companies.

Yet at 0.18% a year, the Dimensional ETF is still pricier than some broad-market index funds that capture a swath of international stocks for under 10 basis points annually. Market-cap-weighted ETFs such as Gold-rated Vanguard Total International Stock ETF VXUS or iShares MSCI ACWI ex US ETF ACWX pull in much of the investable universe outside of the US for a razor-thin fee. What these funds lack in flexibility, they make up for with a broad scope that doesn’t miss out on unexpected winners.

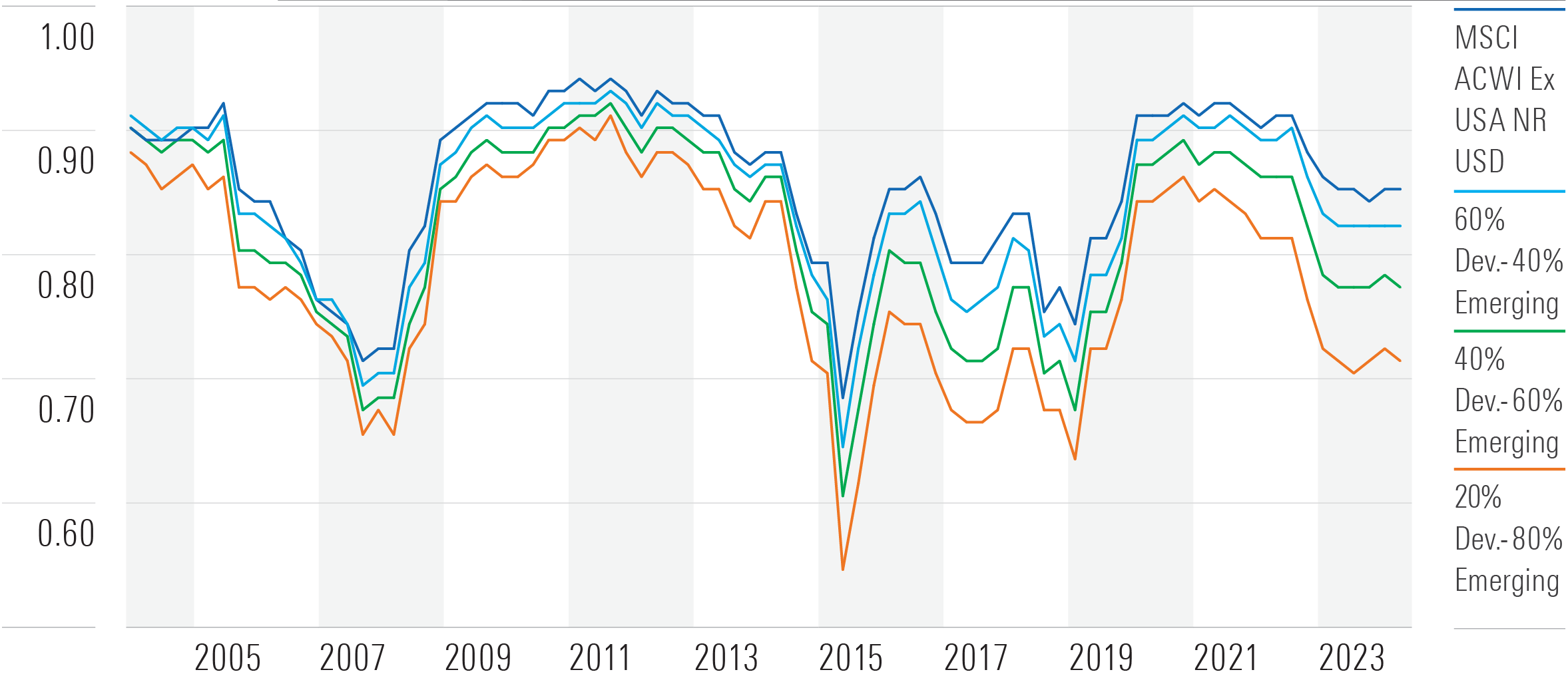

While straightforward and inexpensive, this approach does lump together the whole international ex US market. We’re implicitly letting market capitalization decide the divide between emerging- and developed-markets stocks. The allocation has stood at roughly 20% for emerging-markets stocks and 80% for developed-markets stocks in the past decade. This mix might represent where global investors are pouring their money, but is it optimal? Emerging-markets stocks offer more diversification benefit to a US stock portfolio, but they also come at the expense of more dramatic swings. Exhibit 3 explores the incremental benefits of amping up our emerging-markets allocation compared with a market-cap-weighted index, the MSCI All World ex USA Index. The test portfolios use the MSCI EAFE and MSCI Emerging Markets indexes as underlying securities.

Upping the emerging-markets stake increased the volatility of the international-stock sleeve but lowered its correlation to the US stock market. An 80% allocation to emerging markets brings correlation to the S&P 500 down to 0.78, at the expense of a 3-percentage-point increase in standard deviation of returns compared with the market-cap-weighted index.

A more reasonable alternative was around a 40% allocation to emerging-markets stocks within the international-stock sleeve. The additional volatility didn’t detract significantly from risk-adjusted return compared with the MSCI All World ex USA Index but improves its diversification benefit for US-centric investors. The Sharpe ratio of the 60% developed/40% emerging portfolio hewed close to the MSCI All World ex USA Index on a rolling three-year basis, even during stressed markets like the 2015 oil price crisis. The maximum drawdown for this allocation was around 58.5% versus 57.6% for the index during the global financial crisis (the S&P 500 lost 51%, for comparison). Nonetheless, there’s no guarantee that history will repeat itself, especially given the limited track records of these indexes. Given the level of idiosyncratic and geopolitical risks present in developing economies, investors shouldn’t view their diversification benefit in isolation. Regardless, investing abroad may offer investors a helping hand the next time US stocks falter.

This article first appeared in the July issue of Morningstar ETF Investor. Click here for a complimentary copy.