The landscape of investing has undergone a seismic shift, with the advent of commission-free trading and low-cost ETFs. While this has empowered retail investors, it has also introduced new challenges. Fees have been significantly reduced, but investors now face less visible but equally harmful costs associated with increased risk.

Vanguard founder John Bogle‘s “cost matters hypothesis” (CMH) was based on the mathematical truth that the sum of all active portfolios equals the market portfolio. From this it follows that the average return on all active portfolios must equal the market return, minus the fees charged by active investment managers. This may have been the single most powerful argument driving the relentless growth of indexing over the past 30 years. However, now that trading and investment fees have gotten close to zero, the CMH has lost its power to direct investors toward low cost, diversified index investing.

Risk matters

From discussions with family, friends, and online investor forums, we’ve noticed it’s become much harder to convince people to avoid frenetic trading of their personal accounts now that trading appears to be “free.” As we scratched our heads over this problem, we realized that the logic underlying Bogle’s CMH applies with equal force in the dimension of risk.

We recently published a paper that puts forward the “risk matters hypothesis” (RMH), a corollary to Bogle’s CMH. The RMH asserts that the average risk across all active portfolios is greater than the risk of the market portfolio. It cautions investors with concentrated stock portfolios that—in aggregate—they must suffer a lower return-to-risk ratio (a.k.a. Sharpe ratio) than they’d get from a broadly diversified index fund. It was an idea we couldn’t find in any personal finance books or textbooks—which surprised us given its significance and simplicity.

The return-to-risk ratio is very important because taking risk is the price we pay for the promise of higher returns. Investors should seek the portfolio with the highest return-to-risk ratio possible, to get as much expected return as they can for a given amount of risk.

Buffett’s warning

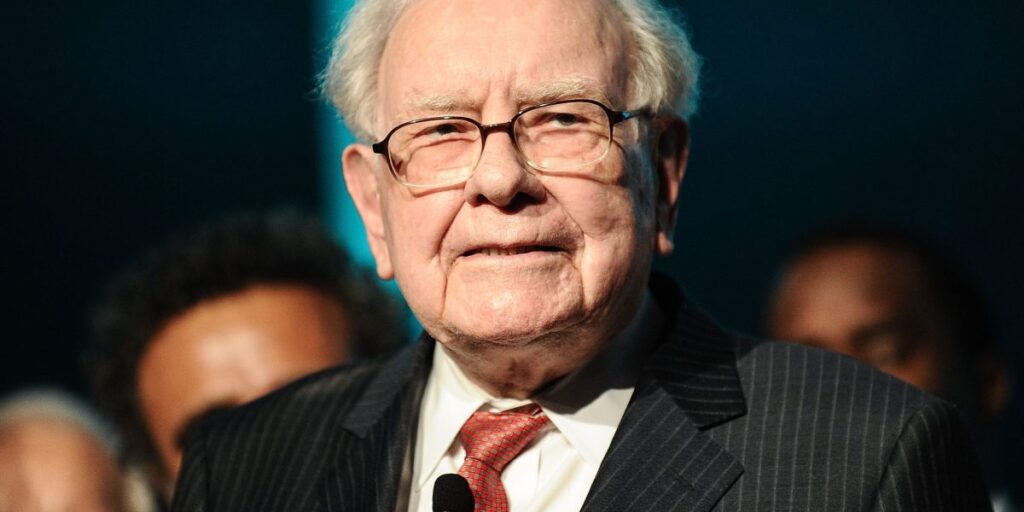

In today’s “free” investing world, many in the finance industry seem bent on distracting investors from this goal. Investors who have not (yet) embraced broad market indexing are being encouraged to trade more actively and take more risk. As Warren Buffett observed, “markets now exhibit far more casino-like behavior than they did when I was young. The casino now resides in many homes and daily tempts the occupants.”

This casino-fication of markets can be seen in the explosion of stock options trading volumes, particularly in lottery-like zero-day-to-expiration options, and the glorification of day-trading on online trading platforms that are almost indistinguishable from online gambling sites. All sorts of leveraged, concentrated, and options-based ETFs have come to market, and have attracted hundreds of billions of dollars in short order.

All these active bets made by retail investors require other market participants, often professional and highly profitable trading firms, to hold opposing active positions. In aggregate, all the players— retail and professional—with holdings that deviate from the market portfolio are taking more risk. And, in aggregate, they need to be compensated for this increased risk by outperforming the market. Unfortunately, this is a mathematical impossibility—the average cannot exceed the average (just as most drivers cannot be above average)!

Taking extra risk can be thought of as equivalent to paying fees; both reduce the expected return-to-risk ratio of the investor’s portfolio, as can be seen in the equation below.

Using reasonable inputs, for return and market risk, we find that a portfolio that has 4% extra active risk is as attractive as one with just market risk but paying a fee of 1%. In this new low-cost investing world, the price active investors pay has shifted from fees to risk.

Double-whammy for active investors

Unfortunately, the bad news for ordinary investors doesn’t stop here. When retail investors take on extra risk, the market participants taking the other side of their active bets are also, on average, taking extra risk. These professional trading firms need to make extra returns to compensate them for the extra risk they’re taking, and the only place that can come from is the pockets of active retail traders. This is a double whammy for active investors—they need to get extra return for the extra risk they take, but instead they wind up with a lower return, because other market participants higher up in the food chain are making extra returns at their expense. While the payment of fees can be thought of as a zero-sum transfer in that one party pays a fee and the other party receives the fee, the cost of taking extra risk is a negative sum phenomenon across all parties.

While the allure of “free” investing is strong, the “risk matters hypothesis” reminds investors to be cautious about the risk associated with deviating from the market. In most cases, the best bet may be to stick with broadly diversified index funds.

The opinions expressed in Fortune.com commentary pieces are solely the views of their authors and do not necessarily reflect the opinions and beliefs of Fortune.