Editor’s note: this article is the second in a series about a pivotal moment in St. Louis’s sustainable transportation evolution, and how it mirrors similar moments in other U.S. cities. Click here to read the entire series.

Over the next three years, St. Louis will receive a deluge of more than $300 million for sustainable transportation projects aimed at increasing multimodal access, calming traffic, and building out the city’s protected bike lane network to a scale never seen before. Much of that money, though, is flowing from one-time federal grants and once-in-a-lifetime infusions of cash from the COVID-era American Rescue Plan Act – and some fear that the the current structure of the local government isn’t set up to build on that momentum once the funds dry up.

Michael Browning is one of them. In 2023, when he was elected to the St. Louis Board of Aldermen – which essentially serves as the city council and its core legislative body — Browning was stunned to learn how transportation decisions were made by local government, which, like many smaller U.S. cities, has never had a formal department of transportation tasked with taking a birds-eye view over community mobility decisions.

In the absence of that department, he says the diffuse and sometimes confusing system the city relies on now has left wide gaps in its safety strategy, even when individual leaders manage to push great projects through. And once the $300 million is exhausted, he worries those gaps will be even more glaring.

“It struck me that there was no department at our city that was primarily concerned with the safety of our roads,” he said. “And what that means is that, over and over again, roads are designed for cars, and not for people.”

The case for Prop T

Browning has since become the driving force behind Proposition T, a controversial measure on the November ballot which will allow Gateway City voters to decide whether to change the name, scope and duties of the Department of Streets to create the first formal DOT in St. Louis history.

Like Oakland, Atlanta, and Louisville before it, Browning hopes that establishing that new transportation-focused agency will centralize St. Louis’s fragmented mobility planning priorities, and let residents know exactly who to call to demand change when traffic violence surges. And most critically, that new department would be held responsible for “programs relating to safe travel for all modes of transportation” [emphasis ours] — making it explicit that moving cars quickly isn’t their primary goal.

Some argue that by the time those changes go into effect in 2029, they’ll be 115 years overdue.

Back when the 1914 charter was first written — just six years after the release of the first Model T, and before women or people of color gained the right to vote — St. Louis was home to a wildly different transportation network, where automobiles were rare and the fast-growing streetcar network was on pace to reach 485 miles of track by the 1920s.

The Streets Department created under that charter was responsible for things like “sprinkling” dirt roads to stop horse-drawn carriages from kicking up too much dust and collecting “ashes” from the fireplaces residents still used to cook and heat their homes.

As that streetcar system was ripped out and automobiles clawed space away from draft animals and pedestrians, some say the de facto focus of the St. Louis transportation system shifted towards facilitating fast, convenient travel for drivers, even if the charter didn’t change. The Streets Department, meanwhile, remained the city’s core road maintenance agency, and shifted its responsibilities towards striping lane markings and patching potholes caused by an endless stream of ever-heavier cars and trucks.

But who decides exactly how those streets should look and function today has become a far stickier question over the course of the last century.

Browning explains that task usually falls to some combination of the Board of Public Services, the city’s Planning and Urban Design Agency, and the loose army of outside firms to which they contract much of their work, including many of the grant-funded signature projects that make up most of the current $300-million haul.

But he says alderpeople like him hold an outsized influence, too, because they control much of the city’s core road funding, including the oft-debated “ward capital system” that guarantees each alder a small pot of money to spend on neighborhood improvements every year. Alders maintain control over that funding even if some of them don’t actually spend any of it on road safety projects for years on end; others can’t save up enough money to cover their wards’ dire road safety needs before their time in office runs out or they lose an election.

Alderpeople are also responsible for passing the budget for a second, little-known road fund called St. Louis Works, which is supposed to pay for sidewalks, road repair and more. That process, though, once languished for more than two years straight — and a city staffer said the stall left $9.8 million on the table, even as roads crumbled and more than a hundred road users lost their lives.

“Not everyone on the Board is saying, ‘How can I make my streets safer?’ even if there is terrible crash data coming out of their ward,” Browning adds. “And the other side of that is that we’re … dividing our funding up on a ward-by-ward basis, which means that every ward gets the same amount of money, even if their roads are more dangerous, or if they just have more roads to take care of. So that’s an incredibly inequitable way of doing it — and it translates to our streets being extremely dangerous, because we’re not making decisions in a comprehensive way.”

That virtually none of those alderpeople has any background as traffic safety professionals, Browning says, doesn’t dissuade residents from demanding safer streets from elected like him — because they simply don’t know who else to call. Browning himself worked as a grant specialist at a local university’s ophthalmology department before he was elected, which is a far cry from executing life-saving infrastructure projects.

“If you’re confused, well, that’s kind of the point of this reform,” Browning added. “Right now, there’s not a clear answer as to who is in charge of making our streets safer.”

The case against Prop T

Within the halls of city government, though, Prop T has proven to be a magnet for controversy — and some have argued that it wouldn’t really solve the city’s transportation challenges.

Chief among those concerns is that Prop T itself won’t actually abolish the ward capital system that Browning and others criticize and direct it to the new DOT, much less increase the core funding that the DOT would need to save lives at any significant scale.

One of the biggest expenses of all might be staff, who city agencies are already struggling to hire even as a tidal wave of $300 million comes crashing over the transportation system. The hypothetical DOT would also be responsible for a dizzying array of transportation priorities that haven’t always fallen under those agencies’ purview, including transit, the regulation of shared micromobility operators, and off-road trails.

In August, Mayor Tishaura Jones — who has publicly championed the city’s upcoming multimodal initiatives — declined to sign the board bill that added Prop T to the ballot, with a spokesperson telling St. Louis Public Radio that “real change requires in-depth discussion with departments around reform for more predictable funding streams and long-term capital planning.”

Scott Ogilvie — Jones’s Complete Streets manager, and a former alderperson himself who is well aware of the current systems’ challenges — was even more blunt in a July 30 Aldermanic committee meeting about the bill.

“We don’t want a Department of Transportation that does not have the capacity to do the things the charter would require it to do,” Ogilvie said. “And the responsibilities in this bill, in this charter amendment, significantly increase the important responsibilities of that department. As a staff person, I think we cannot emphasize enough how challenging it may be to hire the people into this department necessary to perform these functions.”

Browning, who originally wanted the new DOT to be put in place by 2027, agreed to delay the implementation of Prop T to 2029, giving the city time to build its massive slate of upcoming infrastructure projects before radically reworking its core structure. He argues that will give the city plenty of time to craft follow-up ordinances and studies that detail exactly how the new transportation agency will work, who will work there, and how much the city will actually need to pay to attract the talent they need.

“We cannot do something the same way for 110 years and change it overnight,” Browning added. “We have to do incremental changes in order to walk us towards a better system.”

Some, though, argue that St. Louis can get safer without upsetting a 110 year-old apple cart — because it’s doing it right now.

The $300 million in funded infrastructure projects, after all, were won by the same diffuse system that Browning and his co-sponsors want to rewrite; the new Transportation and Mobility Plan that the city is currently crafting could help ensure that structure continues to deliver good projects, and better safety outcomes for all road users.

“I did the numbers this morning; the dollars going through [the Board of Public Service] today are five, six, seven times as much transportation spending … in the next couple of years as was typical a few years ago,” added Ogilvie at the July 30 meeting. “All of that, with a safety, multimodal, accessibility focus, 100 percent across the board. I think everybody here has the desire and necessity for change. … But the idea that there will be one place you can go to to get an answer to all your [transportation] questions? The answer might just be ‘no’ if the department doesn’t have the staff [it needs.]”

‘Who is responsible?’

Browning acknowledges that, DOT or no, St. Louis is achieving big wins for sustainable transportation — and it may well continue to do so even if Prop T doesn’t pass.

When safety champions like Jones and Ogilvie leave government someday, though, he wants to ensure that the city is required to find strong new leaders to carry on their legacy — or at least one person with whom the buck stops.

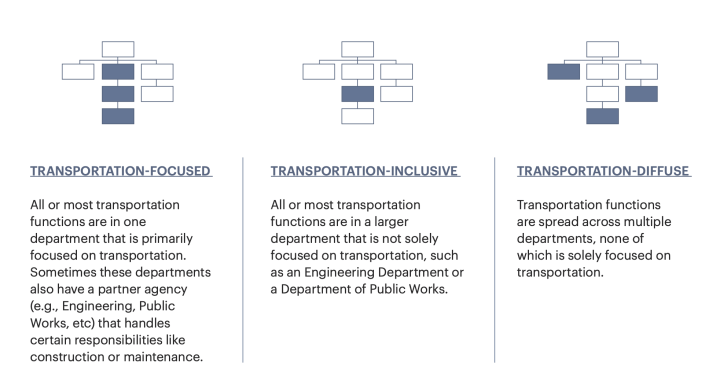

“The weakness of ‘transportation diffuse’ structures like ours is that there is no one clearly in charge of the system,” Browning adds. “It really depends on a champion somewhere in the government to unify those different structures towards a common goal… What people should be asking is, ‘Who in your city is responsible for the safety of people on your streets?’ Because at the end of the day, that’s what matters.”

St. Louis will find out on Nov. 5 whether voters share his view. What Ogilvie and Browning can both agree on in the meantime, though, is that Gateway City residents are ready for a new vision for transportation safety, with leaders taking a holistic view of its traffic violence crisis — and taking urgent action to end it citywide.

How the state of Missouri can support them in that effort, though, is a separate question. We’ll tackle that when this series continues later this week.