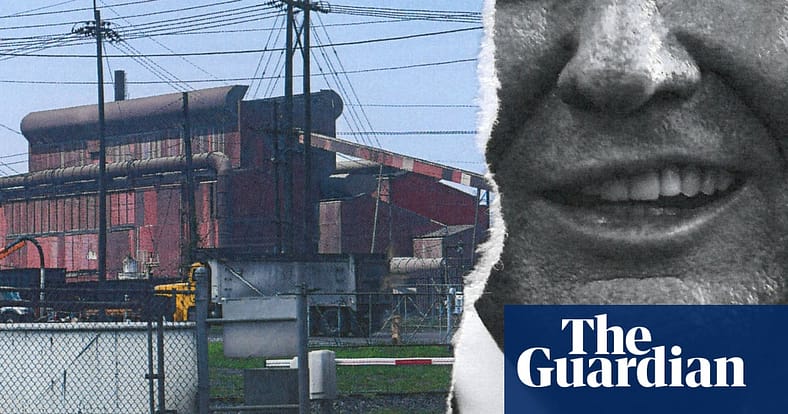

A hulking steel plant in Middletown, Ohio, is the city’s economic heartbeat as well as a keystone origin story of JD Vance, the hometown senator now running to be Donald Trump’s vice-president.

Its future, however, may hinge upon $500m in funding from landmark climate legislation that Vance has called a “scam” and is a Trump target for demolition.

In March, Joe Biden’s administration announced the US’s largest ever grant to produce greener steel, enabling the Cleveland-Cliffs facility in Middletown to build one of the largest hydrogen fuel furnaces in the world, cutting emissions by a million tons a year by ditching the coal that accelerates the climate crisis and befouls the air for nearby locals.

In a blue-collar urban area north of Cincinnati that has long pinned its fortunes upon the vicissitudes of the US steel industry, the investment’s promise of a revitalized plant with 170 new jobs and 1,200 temporary construction positions was met with jubilation among residents and unions.

“It felt like a miracle, an answered prayer that we weren’t going to be left to die on the vine,” said Michael Bailey, who is now a pastor in Middletown but worked at the plant, then owned by Armco, for 30 years.

“It hit the news and you could almost hear everybody screaming, ‘Yay yay yay!’,” said Heather Gibson, owner of the Triple Moon cafe in central Middletown. “It showed commitment for the long term. It was just so exciting.”

This funding from the Inflation Reduction Act (IRA), the $370bn bill to turbocharge clean energy signed by Biden after narrowly passing Congress via Democratic votes in 2022, has been far less thrilling to Vance, however, despite his deep personal ties to the Cleveland-Cliffs plant.

The steel mill, dating back to 1899 and now employing about 2,500 people, is foundational to Middletown, helping churn out the first generations of cars and then wartime tanks. Vance’s late grandfather, who he called Papaw, was a union worker at the plant, making it the family’s “economic savior – the engine that brought them from the hills of Kentucky into America’s middle class”, Vance wrote in his memoir, Hillbilly Elegy.

But although it grew into a prosperous All-American city built on steel and paper production, Middletown became a place “hemorrhaging jobs and hope” as industries decamped offshore in the 1980s, Vance wrote. He sees little salvation in the IRA even as, by one estimate, it has already spurred $10bn in investment and nearly 14,000 new jobs in Ohio.

When campaigning for the Senate in 2022, Vance said Biden’s sweeping climate bill is “dumb, does nothing for the environment and will make us all poorer”, and more recently as vice-presidential candidate called the IRA a “green energy scam that’s actually shipped a lot more manufacturing jobs to China”.

America needs “a leader who rejects Joe Biden and Kamala Harris’s green new scam and fights to bring back our great American factories”, Vance said at the Republican convention in July. “We need President Donald J Trump.”

Republicans in Congress have repeatedly attempted to gut the IRA, with Project 2025, a conservative blueprint authored by many former Trump officials, demanding its repeal should Republicans regain the White House.

Such plans have major implications for Vance’s home town. The Middletown plant’s $500m grant from the Department of Energy, still not formally handed over, could be halted if Trump prevails in November. The former president recently vowed to “terminate Kamala Harris’s green new scam and rescind all of the unspent funds”.

Some longtime Middletown residents are bemused by such opposition. “How can you think that saving the lives of people is the wrong thing to do?” said Adrienne Shearer, a small business adviser who spent several decades helping the reinvigoration of Middletown’s downtown area, which was hollowed out by economic malaise, offshored jobs and out-of-town malls.

“People thought the plant was in danger of leaving or closing, which would totally destroy the town,” she said. “And now people think it’s not going anywhere.”

Shearer, a political independent, said she didn’t like Vance’s book because it “trashed our community” and that he had shown no alternative vision for his home town. “Maybe people who serve with him in Washington know him, but we don’t here in Middletown,” she said.

Climate campaigners are even more scathing of Vance. “It’s no surprise that he’s now threatening to gut a $500m investment in US manufacturing in his own home town,” said Pete Jones, rapid response director at Climate Power. “Vance wrote a book about economic hardship in his home town, and now he has 900 new pages from Trump’s dangerous Project 2025 agenda to make the problem worse so that big oil can profit.”

Local Republicans are more complimentary, even if they differ somewhat on the IRA. Mark Messer, Republican mayor of the neighboring town of Lebanon, used the vast bill’s clean energy tax credits to offset the cost of an upcoming solar array that will help slash energy costs for residents. Still, Vance is a strong running mate for Trump and has “done good for Ohio”, according to Messer.

“My focus is my constituents and doing what’s best for them – how else will this empty floodplain produce $1m for people in our town?” Messer said. “Nothing is going do that but solar. I’m happy to use the IRA, but if I had a national role my view might be different. I mean printing money and giving it away to people won’t solve inflation, it will make it worse.”

Some Middletown voters are proud of Vance’s ascension, too. “You have to give him credit, he went to [Yale] Law School, he built his own business up in the financial industry – he’s self-made, he did it all on his own,” said Doug Pergram, a local business owner who blames Democrats for high inflation and is planning to vote for Trump and Vance, even though he thinks the steel plant investment is welcome.

This illustrates a problem for Democrats, who have struggled to translate a surge of new clean energy projects and a glut of resulting jobs into voting strength, with polls showing most Americans don’t know much about the IRA or don’t credit Biden or Harris for its benefits.

Ohio was once a swing state but voted for Trump – with his promises of Rust belt renewal that’s only now materializing under Biden – in the last two elections and is set to do the same again in November. Harris, meanwhile, has only fleetingly mentioned climate change and barely attempted to sell the IRA, a groundbreaking but deeply unsexy volume of rebates and tax credits, on the campaign trail.

“Democrats have not done well in patting themselves on the back, they need to be out there screaming from the rooftops, ‘This is what we’ve done,’” said Gibson, a political independent who suffers directly from the status quo by living next to the Middletown facility that converts coal into coke, a particularly dirty process, that will become obsolete in the mill’s new era.

“The air pollution is horrendous, so the idea of eliminating the need for coke, well, I can’t tell you how happy that makes me,” said Gibson. The site, called SunCoke, heats half a million short tons of coal a year to make coke that’s funneled to the steel plant, a process that causes a strong odor and spews debris across the neighborhood. Gibson rarely opens her windows because of this pollution.

“Last year it snowed in July, all this white stuff was falling from the sky,” Gibson said. “The soot covers everything, covers the car, I have to Clorox my windows. The smell is so bad I’ve had to end get-togethers early from my house because people get so sick. It gives you an instant headache. It burns your throat, it burns your nose. It’s just awful.”

The prospect of a cleaner, more secure future for Middletown is something the Biden administration tried to stress in March, when Jennifer Granholm, the US energy secretary, appeared at the steel mill with the Cleveland-Cliffs chief executive, union leaders and workers to extol the new hydrogen furnace. The grant helps solve a knotty problem where industry is reluctant to invest in cleaner-burning hydrogen because there aren’t enough extant examples of such technology.

“Mills like this aren’t just employers, they are anchors embedded deeply in the community. We want your kids and grandkids to produce steel here in America too,” Granholm said. “Consumers are demanding cleaner, greener products all over the world. We don’t want to just make the best products in the world, we want to make sure we make the best and cleanest products in the world.”

Lourenco Goncalves, chief executive of Cleveland-Cliffs, the largest flat-rolled steel producer in North America, followed Granholm to boast that a low-emissions furnace of this size was a world first, with the technology set to be expanded to 15 other company plants in the US.

Republicans elsewhere in the US have jumped onboard similar ribbon-cutting events, despite voting against the funding that enables them, but notably absent among the dignitaries seated in front of two enormous American flags hanging in the Middletown warehouse that day was Vance, the Ohio senator who went to high school just 4 miles from this place. His office did not respond to questions about the plant or his plans for the future of the IRA.

Bailey, a 71-year-old who retired from the steel plant in 2002, said that as a pastor he did speak several times to Vance about ways to aid Middletown but then became alarmed by the senator’s rightwards shift in comments about women, as well as his lack of support for the new steel mill funding.

“JD Vance has never mentioned anything about helping Middletown rebound,” said Bailey, who witnessed a “brutal” 2006 management lockout of workers during a union dispute after which drug addiction and homelessness soared in Middletown. “He’s used Middletown for, in my view, his own personal gain.

“Somewhere in there, JD changed,” he added. “He’s allowed outsiders to pimp him. This guy is embarrassing us. That’s not who we are.”