Carson Ward knew that asking the Freeway Fighters Network for help advocating against an Amtrak project would be a bit of a stretch.

But as chair of the Reservoir Hill Association’s Baltimore and Potomac Tunnel working group, Ward argues that the specific project she’s fighting bears disturbing similarities to the countless highways that destroyed Black neighborhoods across America — and that it’s time for sustainable transportation advocates to get involved.

“While I understand that the preference is public transit over highways, public transit should work for the community instead of gentrifying or harming it,” Ward wrote to the group’s listserv. “And Amtrak could have achieved its project goals using less discriminatory alternatives.”

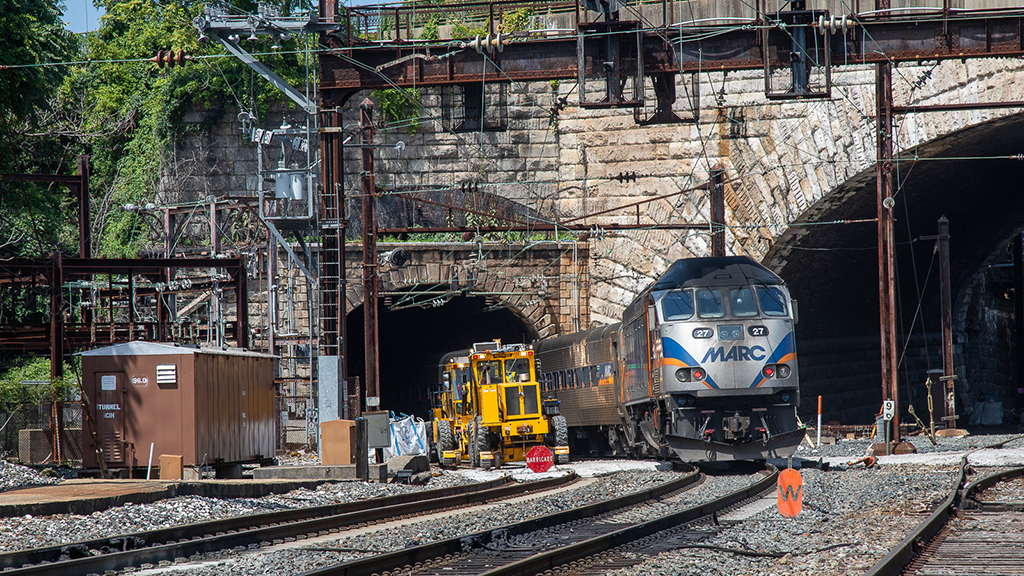

That project is the Frederick Douglass Tunnel Program, a $6-billion effort to replace and modernize the 151-year-old Baltimore and Potomac Tunnel that runs underneath part of the western half of the city — and the largest single project in Amtrak’s infrastructure portfolio right now.

Amtrak says the floor of the aging tunnel has sunk, and water has crept through the masonry, requiring constant, expensive maintenance. The tunnel’s tight curves, meanwhile, have forced the hundreds of passenger, freight, and regional commuter trains that pass through it every day to slow to just 30 miles per hour, causing delays on virtually every weekday.

Advocates of the project like Maryland Gov. Wes Moore argue that replacing the B&P with the Frederick Douglass Tunnel and changing its route to soften those sharp curves would alleviate one of the worst bottlenecks in the Northeast Corridor, that it would reduce noise and pollution in the community by serving primarily electrified passenger trains, and that it would bring $50 million in community investments with it. Moore called the project a “transformative investment” that would “help us deliver a world-class transportation network for our residents, our business community and the entire region.”

Some residents of Reservoir Hill, though, fear that building that “world-class” future will create years of disruptions in their neighborhood — and when that future finally arrives, they might not be around to enjoy it.

“We view the project as a continuation of the history of using black communities as sacrifice zones for American infrastructure,” said Keondra Prier, president of the Reservoir Hill Association, which filed a formal civil rights complaint against the project in April. “And this history is something that has happened over many, many decades. … This is yet another example of the many proposals for infrastructure that disproportionately harm Black and low-income communities, and this project can be done in a different way.”

Reservoir Hill Speaks Out

Prier’s concerns about the Frederick Douglass project could be a harbinger of future fights to come across the U.S. if and when rail networks expand — and in some ways, it’s also an eerie echo of freeway battles past.

In their sprawling 36-page complaint, lawyers for the Association compared the Frederick Douglass project to the infamous “Highway to Nowhere,” when transportation officials displaced roughly 1,500, majority-Black, Baltimoreans to build a highway connection that was never even completed.

The new tunnel, they say, would similarly require Amtrak to “demolish and acquire hundreds of homes and businesses in majority-Black neighborhoods,” including several in Reservoir Hill. They also point out that the tube’s new route essentially curves past a series of majority-white neighborhoods in order to carve through theirs, potentially decreasing the time savings value of the entire project.

All of Amtrak’s 14 proposed route alternatives ran through predominantly Black areas.

“Amtrak is proposing to basically cut through and displace residents only in majority Black communities,” Ward added in a follow-up interview. “They will bulldoze through the heart and the soul of our communities.”

Those demolitions, the complainants argue, would be only the latest injuries suffered by a neighborhood that’s already endured decades of white flight, red-lining, and harmful transportation projects like Interstate 83, which bounds Reservoir Hill to the east and has functionally divided residents from predominantly white neighborhoods nearby.

Like many highway projects, the Frederick Douglass program will also cost some residents their homes, businesses, a medical center, and multiple houses of worship. They also claim those property owners aren’t being paid fairly, given all they’ll lose to the bulldozers, especially since many of those sites represent the few remaining community services remaining in Reservoir Hill’s borders.

Last year, the Washington Post reported that 29 residential properties and 19 commercial properties, not all of which were in Reservoir Hill, had been acquired for demolition by Amtrak for just $267,500 — combined.

“They’re kind of dotting the i’s and crossing the t’s on segregation with this project,” added Prier. “They’re demolishing the only remaining commercial properties on one of the largest corridors in the neighborhood, which eliminates even the possibility of someone opening a store or opening a pharmacy there.”

As their neighborhood loses opportunities to build walkable destinations, Prier and her co-complainants say that past transportation “investments” are still raining car pollution down over them, giving residents some the worst rates of pediatric asthma hospitalizations and air quality in the state of Maryland. And while the Frederick Douglass project certainly wouldn’t put any more cars on the road, it would require the construction of a new emergency ventilation facility in Reservoir Hill, which they worry “has the potential to expose community members, including children at the nearby elementary school, to harmful emissions.”

For Ward and the 2,000 people who have signed a petition to relocate the ventilation facility, those impacts are unacceptable — especially for a project named for one of the most important civil rights leaders of all time.

“Now, in the year of the 60th anniversary of passing the Civil Rights Act of 1964, here we are fighting the same structural racism, proven to unjustly decimate Black communities, which we are supposed to be protected from in this day in age,” she wrote in the complaint. “President Biden promised he would put environmental justice at the center of what he does. This is the exact opposite of that promise.”

Amtrak answers

Amtrak officials, though, paint a very different picture of what the Frederick Douglass Tunnel will mean for Reservoir Hill — and they say many of the residents’ concerns are the result of simple misunderstandings.

For instance, they say the emergency ventilation facility is only being built to extract smoke and give passengers an evacuation route in the very rare event of a fire, and it wouldn’t cause poor air quality in the region on a normal day, since the new tunnel is “designed for all-electric passenger trains” — not the diesel-powered trains that run through the B&P now. (The complainants claim, though, that past Amtrak communications have kept open the possibility of adding diesel freight service later, and that they haven’t definitively ruled that option out.)

The agency also says the properties they’re acquiring are almost entirely subterranean, with fewer than 100 located above ground — a major impact, to be sure, but a far cry from the scale of devastation that follows a typical downtown freeway construction. And while those demolitions may be painful, they say they’ve made extensive efforts to engage the community throughout the process and keep them involved.

“We are committed to doing the right thing, and that includes working with community members through every stage of the Frederick Douglass Tunnel Program,” Amtrak spokesman W. Kyle Anderson said in a statement to Streetsblog. “From the start of the environmental review process for the [tunnel] in 2014, Amtrak supported the Federal Railroad Administration and the Maryland Department of Transportation across extensive community outreach and public comment opportunities before the final Program alignment and other details were approved in 2017.”

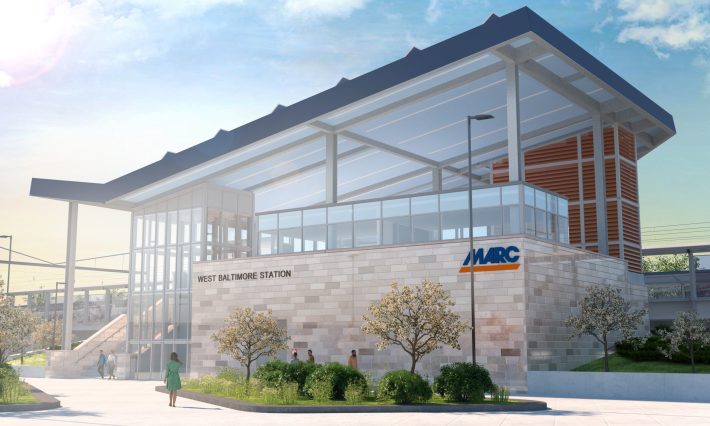

Those “hundreds of outreach engagements,” Amtrak said, are continuing to shape the Frederick Douglass program, including $50 million in community investments in West Baltimore that will grant to community organizations money that can be used for new bus stop seating, after-school programs for kids and other benefits. The project will also incorporate a new ADA accessible commuter rail station in West Baltimore while adding new bridges, repaving roads, and more.

And more to the point, proponents of the Frederick Douglass tunnel argue that making passenger trains faster and more reliable is a critical part of reducing car dependency — not just in Baltimore, but along the entire East Coast.

‘Why do I keep fighting?’

For the residents of Reservoir Hill, though, it’s hard to understand why their community should be shouldering the burden for the greater good of America’s transportation system — at least without Amtrak taking more steps to mitigate their concerns.

Rather than calling on the agency to cancel the Fredrick Douglass project outright, the complainants have asked the agency to halt its construction “until it has clearly and conclusively addressed Reservoir Hill residents’ concerns,” including moving the ventilation facility, conclusively ruling out any future freight travel, increasing the scale of their community investments, and letting residents have a say in how that money is spent.

Most important, those community engagement sessions should be more meaningful than just giving residents a say in the design of the windows on the ventilation facility, as Amtrak did in May “to increasingly audible gasps and groans” from residents, the Baltimore Sun reported.

“We are not anti-transit, and we’re not calling for this project to be fully stopped,” emphasizes Ward. “We are just calling for this project to be more equitable … It’s just the way that Amtrak has come into the community, and the ways in which they disregarded our rights and federal laws.”

Prier hopes Reservoir Hill’s story can spark a conversation about the cumulative harm that’s been caused to Black communities by American infrastructure projects and policies across decades, even when those efforts were intended to boost sustainable modes. And that harm can take many forms that aren’t easily quantified.

“When you can’t walk to work, when you’re living through decades of construction, when they’re literally pressuring you to sell the land beneath your feet, when you know that the value of your home is half that of your white neighboring neighborhood solely because of the practices of the government — that’s another type of displacement, right?” she added. “The psychological warfare that we’re all living through, where you wake up every morning and wonder, ‘Is it worth staying? Why do I keep fighting?'”

In the end, the Reservoir Hill Association’s plea to the Freeway Fighters didn’t generate much of a response. But with more massive rail investments coming down the pike across the country — and, sustainable transportation advocates hope, even more on the horizon — some members were pleased to see Ward start a conversation about how the group’s mission could expand beyond their car-focused name, and help rail projects set the standard for true mobility justice rather than replicating the mistakes of the past.

“It’s always easy to approach these issues in a vacuum: ‘Trains good, highway bad,'” said Ben Crowther of America Walks, who helped found the Freeway Fighters. “But [this story] strikes me as similar to how we think and talk about highway removal and reclaiming neighborhoods from car infrastructure.

“In a vacuum, it’s always great to dismantle highways in our neighborhoods. But at the same time, we have the ask the question: who’s benefiting from those infrastructure projects? And are those benefits being channeled to residents who are living there currently? Are they reparative to the people who were displaced? … It would be great to see Freeway Fighters take up more fights like this.”